In the study of classical mechanics, understanding the state of a moving object at any specific moment is crucial for predictive modeling. Kinematics provides the mathematical framework required to describe this motion without necessarily investigating the underlying forces. This scientific analysis typically begins by identifying the initial parameters of the system, such as speed and orientation. This foundational step allows us to define the starting environment for any vehicle Final Velocity after Braking calculation.

On This Page

- Distinguishing Acceleration and Retardation

- Mathematical Execution of the Braking Calculation

- Kinematics and the Idea of Instantaneous State

- Distinguishing Acceleration and Retardation

- Selecting the Appropriate Equation of Motion

- Step-by-Step Braking Calculation

- Key Variables in the Braking Problem

- Engineering and Safety Perspective

- Energy Transformation During Braking

- Additional Numerical Problems with Solutions

- Practical Engineering and Safety Applications

We Also Published

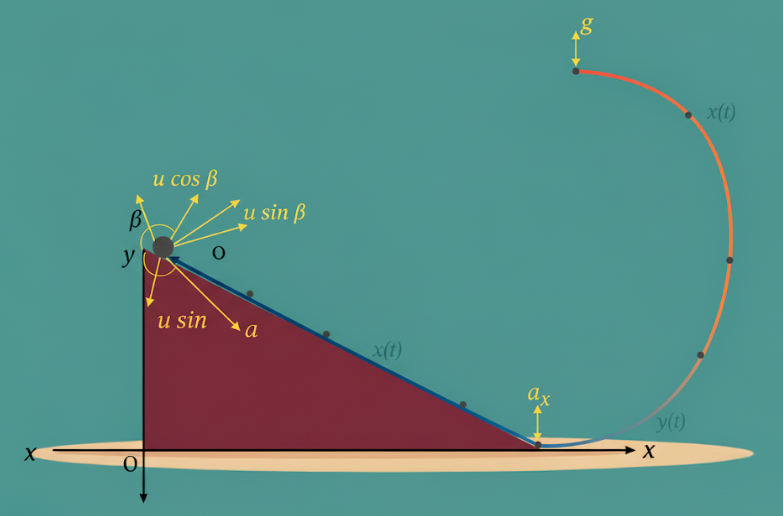

For our specific problem, we begin with an initial velocity, commonly denoted by the variable ##u## in physics equations. This value represents the rate of displacement at the exact moment the observation begins, which is ##20\text{ m/s}## in this instance. This velocity is a vector quantity, meaning it possesses both magnitude and direction, although we simplify this to one dimension for standard linear problems. Establishing this baseline is essential for all subsequent kinematic deductions.

Time, represented by the variable ##t##, serves as the independent variable in most equations of motion. It measures the duration over which a physical change in velocity occurs within the system. In this scenario, we are examining the behavior of the vehicle over a specific interval of exactly ##3\text{ seconds}##. Without a clear definition of time, it would be impossible to quantify the cumulative effect of the braking force applied to the car.

The relationship between velocity and time is fundamental to predicting the future state of any mechanical system. By accurately establishing these initial conditions, researchers can model the trajectory and speed of objects with high precision. This logical process is a prerequisite for solving any complex numerical problem involving moving bodies. It ensures that the inputs for our mathematical formulas are consistent with the physical reality of the observed event.

Distinguishing Acceleration and Retardation

Acceleration is defined as the instantaneous rate of change of velocity over a given time interval. In most academic contexts, a positive numerical value indicates an increase in speed, while a negative value signifies a decrease. This distinction is vital for maintaining the correct sign convention during the mathematical processing of the problem. Failure to differentiate between these states often leads to incorrect predictions about the final state of an object.

Retardation, often referred to as deceleration, specifically describes the slowing down of an object's motion. In the provided problem, the car decelerates at a constant rate of ##4\text{ m/s}^2##. Mathematically, this is expressed as a negative acceleration, represented as ##a = -4\text{ m/s}^2##. This negative sign indicates that the acceleration vector points in the opposite direction of the car's current velocity vector, effectively opposing the forward movement.

The assumption of constant deceleration implies that the braking force is applied uniformly throughout the entire three-second duration. While real-world braking involve fluctuations due to mechanical or environmental factors, idealized physics problems assume a steady rate for simplicity. This allows for the use of linear kinematic equations that offer high accuracy for short durations. These models provide a reliable approximation of how a vehicle reacts when the driver engages the braking system.

Identifying the correct sign for acceleration is arguably the most common point of error for students. When we use the placeholder "" in our conceptual models, it reminds us to verify that we are treating these values as distinct numerical inputs for analysis. Without the negative sign, the calculation would incorrectly suggest the car is speeding up. Using the correct polarity ensures the final result accurately reflects the vehicle losing speed over time.

Mathematical Execution of the Braking Calculation

Selecting the Appropriate Equation of Motion

To find the final velocity after a specific period of braking, we must choose from the primary equations of motion. These equations relate velocity, displacement, time, and acceleration in various combinations. The choice depends entirely on which variables are provided in the problem statement and which specific value we need to determine. Selecting the wrong formula can lead to unnecessary complexity or the need for extra data that is unavailable.

The first equation of motion, ##v = u + at##, is the most direct tool for solving this specific task. It defines the final velocity, ##v##, as the sum of the initial velocity and the product of acceleration and time. This formula is derived directly from the fundamental definition of acceleration. It is ideally suited for situations where the displacement is unknown and only the change in speed over time is required.

Other kinematic equations, such as ##v^2 = u^2 + 2as##, require knowledge of the total displacement, which is not provided in our initial data. Similarly, the equation ##s = ut + \frac{1}{2}at^2## would only be helpful if we were looking for the total distance traveled during the braking event. Thus, the linear velocity-time relationship is our most efficient path forward. It minimizes the number of steps required to reach the solution.

Accuracy in physics necessitates a meticulous variable mapping process before any computation begins. We must confirm that ##u = 20\text{ m/s}##, ##a = -4\text{ m/s}^2##, and ##t = 3\text{ s}##. With these three known values, the equation ##v = u + at## contains only one unknown variable. This structural clarity transforms the physical problem into a straightforward exercise in algebraic substitution and basic arithmetic operations.

Step-by-Step Computational Analysis

We begin the calculation by substituting the known numerical values into our selected kinematic formula. Substituting ##20## for the initial velocity ##u## and ##-4## for the acceleration ##a##, the equation takes a specific form: ###v = 20 + (-4 \times 3)### This clear substitution ensures that the negative nature of the deceleration is properly integrated into the summation. It prepares the equation for the final arithmetic steps.

The next logical step involves performing the multiplication within the parentheses to determine the total change in velocity. Multiplying the constant deceleration rate of ##4\text{ m/s}^2## by the specified time of ##3\text{ seconds}## yields a total reduction of ##12\text{ m/s}##. This product represents the cumulative effect of the brakes over the entire interval. It quantifies how much speed the vehicle has lost due to the retardation force.

Finally, we subtract this total reduction from the original initial velocity of the vehicle. Subtracting ##12\text{ m/s}## from the starting speed of ##20\text{ m/s}## leaves us with a resulting value of ##8\text{ m/s}##. This numerical result confirms that the car has slowed significantly during the three-second period. However, since the value is still positive, we know the vehicle is still moving forward at a reduced rate.

Visualizing the numerical result helps verify its physical plausibility in a real-world context. If the car loses ##4\text{ m/s}## every second, then after three seconds, it should indeed have lost a total of ##12\text{ m/s}##. Starting at ##20\text{ m/s}## and losing ##12\text{ m/s}## logically results in a remaining speed of ##8\text{ m/s}##. This step-by-step verification confirms the accuracy of our kinematic model and the final answer.

Kinematics and the Idea of Instantaneous State

In classical mechanics, the state of a moving object at any instant is defined primarily by its position and velocity. Kinematics provides a clean mathematical language to describe how these quantities evolve with time, without asking why the motion occurs. This separation is powerful: once the motion is described accurately, deeper force-based analysis can be layered later.

Any braking analysis begins by fixing the initial conditions. For vehicle motion along a straight road, this usually means specifying an initial velocity and a time interval during which braking acts. These parameters define the starting environment for a final velocity after braking calculation and remove ambiguity from the physical situation.

In the present case, the initial velocity is denoted by ##u## and has a value of ##20\text{ m/s}##. Velocity is inherently a vector quantity, but for one-dimensional motion along a straight line, direction can be handled using sign conventions. Establishing this baseline ensures that all later deductions remain physically consistent.

The independent variable in all equations of motion is time, represented by ##t##. Here, braking is applied uniformly over a duration of ##3\text{ s}##. Without specifying time, it would be impossible to quantify how much the velocity changes under braking.

Distinguishing Acceleration and Retardation

Acceleration is defined as the rate of change of velocity with respect to time. Mathematically, it is written as

###a = \frac{\Delta v}{\Delta t}###

A positive acceleration increases speed in the chosen positive direction, while a negative acceleration reduces speed. Retardation (or deceleration) is simply acceleration acting opposite to the direction of motion.

In this problem, the vehicle experiences a constant deceleration of ##4\text{ m/s}^2##. Using sign convention, this is written as

###a = -4\text{ m/s}^2###

The negative sign is crucial. It tells us that the acceleration vector opposes the velocity vector. Missing this sign would incorrectly predict that the vehicle speeds up instead of slowing down.

Assuming constant deceleration idealizes the braking process. Real braking systems fluctuate due to road conditions and mechanical response, but for short intervals, constant acceleration models provide excellent approximations.

Selecting the Appropriate Equation of Motion

Among the standard kinematic equations, the most suitable one must be chosen based on the known and unknown variables. The three commonly used equations are:

- ##v = u + at##

- ##s = ut + \frac{1}{2}at^2##

- ##v^2 = u^2 + 2as##

Since displacement is not required and the goal is to find final velocity, the first equation is the most direct. It directly relates velocity change to acceleration and time.

Step-by-Step Braking Calculation

We now substitute the known values into the equation ##v = u + at##.

### v = 20 + (-4 \times 3)###

The product ##-4 \times 3## represents the total reduction in velocity over three seconds, equal to ##-12\text{ m/s}##.

Subtracting this from the initial velocity gives:

###v = 8\text{ m/s}###

The vehicle is still moving forward, but at a significantly reduced speed. This result aligns with physical intuition: losing ##4\text{ m/s}## each second for three seconds produces a total loss of ##12\text{ m/s}##.

Key Variables in the Braking Problem

| Symbol | Quantity | Value |

|---|---|---|

| u | Initial velocity | 20 m/s |

| a | Acceleration | -4 m/s² |

| t | Time interval | 3 s |

| v | Final velocity | 8 m/s |

Engineering and Safety Perspective

Such calculations are fundamental to automotive safety. Engineers rely on them to estimate stopping speeds, braking distances, and collision severity. Even a modest reduction in final velocity drastically reduces kinetic energy, since energy scales with the square of velocity.

Under adverse conditions like rain or ice, achievable deceleration is much lower. Repeating the same calculation with a smaller magnitude of acceleration immediately shows why stopping distances increase so dramatically in poor weather.

Energy Transformation During Braking

Braking converts kinetic energy into thermal energy through friction. A reduction from ##20\text{ m/s}## to ##8\text{ m/s}## corresponds to a large drop in kinetic energy, which appears primarily as heat in brake pads and discs.

Modern electric vehicles exploit the same kinematic principles but recover part of this energy using regenerative braking, converting kinetic energy back into electrical energy stored in batteries.

Additional Numerical Problems with Solutions

Problem 1

A car moving at ##25\text{ m/s}## decelerates uniformly at ##5\text{ m/s}^2## for ##4\text{ s}##. Find the final velocity.

Solution:

###v = 25 + (-5 \times 4) = 5\text{ m/s}###

Problem 2

A bike slows from ##15\text{ m/s}## to ##3\text{ m/s}## in ##6\text{ s}##. Find the acceleration.

Solution:

###a = \frac{v-u}{t} = \frac{3-15}{6} = -2\text{ m/s}^2###

Problem 3

A truck decelerates at ##2\text{ m/s}^2## from ##18\text{ m/s}##. How long until it stops?

Solution:

###0 = 18 + (-2t) \Rightarrow t = 9\text{ s}###

Problem 4

A train reduces speed from ##30\text{ m/s}## to ##10\text{ m/s}## in ##5\text{ s}##. Find the acceleration.

Solution:

###a = \frac{10-30}{5} = -4\text{ m/s}^2###

Problem 5

A car moving at ##12\text{ m/s}## accelerates uniformly to ##20\text{ m/s}## in ##4\text{ s}##. Find the acceleration.

Solution:

###a = \frac{20-12}{4} = 2\text{ m/s}^2###

Points to remember: Always define sign conventions clearly, select equations based on known variables, and verify results against physical intuition.

Practical Engineering and Safety Applications

Braking Efficiency and Road Safety

Understanding the final velocity after a specific braking duration is critical for modern automotive safety engineering. Engineers use these fundamental calculations to determine the baseline effectiveness of various braking system designs. Knowing how quickly a vehicle can shed speed helps in designing advanced collision avoidance systems and setting appropriate speed limits. This data is essential for ensuring that vehicles can respond safely to unexpected obstacles on the road.

In emergency situations, the difference between a high and low final velocity can be life-saving. If an obstacle is detected at a distance, the goal is to reduce the variable ##v## to zero as quickly as possible. This problem demonstrates that even a relatively short braking period of three seconds can substantially lower the kinetic impact force. Reducing speed effectively lowers the energy involved in potential collisions, thereby increasing passenger safety.

Road conditions play a massive role in determining the achievable deceleration rate for any given vehicle. While our problem assumes a constant rate of ##4\text{ m/s}^2##, wet or icy roads might reduce this value significantly. Calculating the resulting velocities under different environmental conditions allows for better driver education and more robust safety ratings. It helps drivers understand how environmental factors influence their ability to slow down safely.

Modern vehicles utilize sophisticated sensors to perform these kinematic calculations in real-time. By monitoring the actual rate of deceleration, the on-board computer can adjust braking pressure to prevent wheel lockup or skidding. This application of basic physics ensures that the vehicle remains stable while attempting to reach a lower final velocity. These automated systems represent a direct evolution of the kinematic principles explored in introductory physics.

Energy Transformations in Friction Systems

Deceleration is not just a mathematical change in numbers; it represents a profound transformation of physical energy. As the car slows from ##20\text{ m/s}## to ##8\text{ m/s}##, its total kinetic energy is reduced significantly. According to the laws of thermodynamics, this energy cannot simply vanish but must be converted into another form. Understanding where this energy goes is a key aspect of mechanical and thermal engineering.

The primary mechanism for this energy conversion is the friction generated between the brake pads and the rotors. This intense mechanical resistance generates a massive amount of thermal energy. In high-performance vehicles, the heat produced during a ##3\text{ second}## braking maneuver can cause the braking components to glow. Managing this heat is one of the most significant challenges in the design of reliable and durable braking systems.

Material science is essential for managing this heat dissipation effectively in automotive applications. Engineers must select ceramic or metallic composites that can withstand high temperatures without losing their necessary coefficient of friction. Studying the velocity change allows designers to calculate the exact thermal load the system must handle. This ensures that the brakes do not fail even under the stress of rapid and repeated deceleration events.

Future transportation technologies, such as electric vehicles, use regenerative braking to capture this moving energy. Instead of losing the energy as waste heat, the electric motor acts as a generator, converting kinetic energy back into electricity. This modern twist on classical kinematics increases overall vehicle efficiency while performing the same deceleration task. It highlights how ancient physical laws continue to drive innovation in the modern green energy era.

Also Read

From our network :

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/analyzing-trump-deportation-numbers-insights-into-the-2026-immigration-crackdown

- Mastering DB2 12.1 Instance Design: A Technical Deep Dive into Modern Database Architecture

- 98% of Global MBA Programs Now Prefer GRE Over GMAT Focus Edition

- Mastering DB2 LUW v12 Tables: A Comprehensive Technical Guide

- Vite 6/7 'Cold Start' Regression in Massive Module Graphs

- 10 Physics Numerical Problems with Solutions for IIT JEE

- AI-Powered 'Precision Diagnostic' Replaces Standard GRE Score Reports

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/trump-political-strategy-how-geopolitical-stunts-serve-as-media-diversions

- EV 2.0: The Solid-State Battery Breakthrough and Global Factory Expansion

RESOURCES

- Kinematics: Intelligent motion control, the only bankable solution

- Kinematics - Wikipedia

- Kinematics App by Nervous System

- Is learning kinematics considered difficult? : r/robotics - Reddit

- Kinematics - Nervous System

- Solar actuators you can bank on - Kinematics

- Kinematics of the trunk and the lower extremities during restricted ...

- How can I “re-learn” inverse kinematics? : r/robotics - Reddit

- Reliability and Minimal Detectible Change values for gait kinematics ...

- The Association of Scapular Kinematics and Glenohumeral Joint ...

- Differences in kinematics and electromyographic activity between ...

- Kinematics Physical Therapy – Norco Physical Therapist Matt Fujita ...

- Effect of fatigue on knee kinetics and kinematics in stop-jump tasks

- Global plate boundary evolution and kinematics since the late ...

- Changes in lower limb kinematics, kinetics, and muscle activity in ...

2 Comments