Theoretical Foundations of Newtonian Dynamics

The Evolution of Motion Theory

The transition from Aristotelian physics to the modern understanding of classical mechanics represents one of the most significant intellectual shifts in human history. Prior to the seventeenth century, the prevailing view, largely attributed to Aristotle, suggested that motion required the continuous application of a force; in this framework, an object would naturally come to rest if the motive force were removed. This early intuition failed to account for the subtle influence of resistive forces such as air resistance and friction, leading to a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of inertia. It was through the rigorous experimental work of Galileo Galilei and the subsequent synthesis by Isaac Newton that the scientific community recognized motion as a state that persists unless acted upon by an external influence. This conceptual breakthrough allowed for the mathematical description of the universe, laying the groundwork for the analytical tools used to solve contemporary problems involving the acceleration of a block and other macroscopic systems.

On This Page

We Also Published

Central to this evolution was the development of the three laws of motion, which provide a comprehensive framework for dynamics. The first law, or the law of inertia, posits that an object will maintain its state of rest or uniform motion in a straight line unless a net external force is applied. This law defines the inertial frame of reference, a prerequisite for the application of Newton's subsequent principles. In the context of solving for the acceleration of a block on a smooth surface, the first law informs us that the block’s change in state—transitioning from rest to a state of acceleration—is the direct result of an unbalanced force. Newton's work essentially moved physics from a qualitative observation of "tendencies" to a quantitative rigorous discipline where every change in motion is mapped to a specific cause. This paradigm shift enables engineers and physicists to predict the behavior of complex mechanical systems with remarkable precision and reliability.

The historical formalization of these laws culminated in the publication of the Philosophiæ Naturalis Principia Mathematica in 1687. Interestingly, while the modern student is accustomed to the algebraic form ###F = ma###, Newton originally expressed his second law in terms of the rate of change of momentum. He stated that the "alteration of motion" is ever proportional to the motive force impressed. The modern algebraic representation was further refined by later mathematicians such as Leonhard Euler, who transformed Newton's geometric proofs into the analytical equations we use today. Understanding this history is crucial for any student of mechanics, as it highlights that the concepts of force and mass are not merely numbers in an equation but represent a deep philosophical understanding of how matter interacts with its environment. In the problem at hand, we apply these centuries of developed knowledge to a simplified model that captures the essence of linear dynamics.

Defining Mass and Net Force Vectors

To accurately calculate the acceleration of a block, one must first establish a clear definition of the physical quantities involved, most notably mass and force. Mass, in the context of Newtonian mechanics, is defined as a measure of an object's inertia, which is its resistance to changes in its state of motion. It is a scalar quantity, typically measured in kilograms (kg) in the International System of Units (SI). It is vital to distinguish between inertial mass, which appears in Newton's second law, and gravitational mass, which determines the magnitude of the gravitational pull on an object. In almost all classical physics problems, these two are considered equivalent due to the equivalence principle. In our specific case, the block possesses a mass of ##m = 5 \text{ kg}##, which serves as the proportionality constant between the force applied and the resulting acceleration, effectively determining how "difficult" it is to move the object from rest.

Force, on the other hand, is a vector quantity, meaning it possesses both magnitude and direction. The standard unit of force is the Newton (N), defined as the amount of force required to accelerate a one-kilogram mass at a rate of one meter per second squared. Mathematically, this is represented as ##1 \text{ N} = 1 \text{ kg} \cdot \text{ m/s}^2##. When analyzing the dynamics of a block on a surface, we must consider the net force, which is the vector sum of all individual forces acting on the body. While the problem specifies a single horizontal force of ##20 \text{ N}##, a complete physical model would also include the downward force of gravity (weight) and the upward normal force exerted by the surface. Because the surface is horizontal and the block does not move vertically, these vertical forces cancel each other out, leaving the horizontal force as the sole component of the net force vector driving the acceleration.

The relationship between these quantities is elegantly summarized in Newton's second law, often written as ###\vec{F}_{\text{net}} = m \vec{a}###. This equation implies that the acceleration vector points in the same direction as the net force vector. In our scenario, since the force is applied horizontally on a frictionless surface, the acceleration will also be purely horizontal. The simplicity of the equation belies its power; it allows us to bridge the gap between the cause (force) and the effect (acceleration). By isolating the acceleration variable, we can derive the formula ###a = \frac{F}{m}###, which illustrates that acceleration is directly proportional to the applied force and inversely proportional to the mass. This inverse relationship is intuitive: if you apply the same force to a heavier object, it will accelerate less. Mastering this relationship is the first step toward solving more complex problems involving multiple forces, inclines, and variable mass systems.

Detailed Analysis of the Block and Environment

Physical Parameters and System Identification

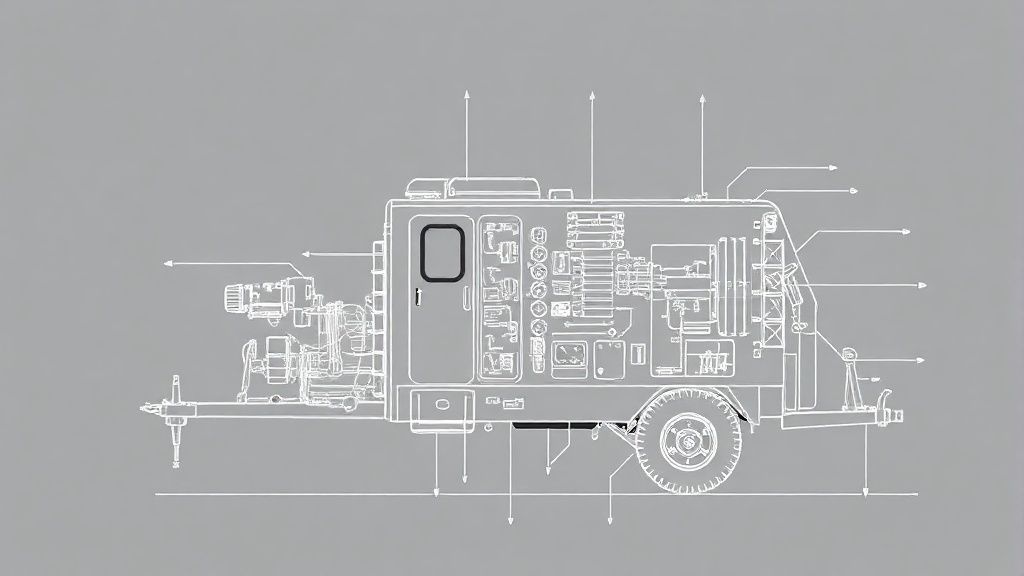

Before proceeding with numerical calculations, it is essential to conduct a thorough analysis of the system parameters. The problem provides two primary pieces of data: the mass of the block and the magnitude of the constant horizontal force. The mass ##m = 5 \text{ kg}## represents the inertial property of the block, while the force ##F = 20 \text{ N}## represents the external influence. In a professional engineering or physics context, identifying these "givens" is the preliminary step in constructing a free-body diagram (FBD). An FBD is a simplified representation where the object is treated as a point mass at its center of gravity, and all external forces are drawn as vectors originating from that point. For this specific block, the horizontal force vector would point in the direction of the push or pull, typically chosen as the positive x-direction for ease of calculation within a Cartesian coordinate system.

System identification also requires an understanding of the constraints acting upon the object. The block is situated on a horizontal surface, which limits its motion to a single dimension. In the vertical y-direction, the force of gravity acts downward with a magnitude of ###W = mg###. For a ##5 \text{ kg}## block, assuming a standard gravitational acceleration of ##g \approx 9.8 \text{ m/s}^2##, the weight would be approximately ##49 \text{ N}##. Simultaneously, the surface exerts an upward normal force ##F_N## that is equal in magnitude to the weight, ensuring that ###\sum F_y = 0###. This equilibrium in the vertical axis is why we can focus entirely on the horizontal forces when determining the block's acceleration. By isolating the horizontal component, we simplify the problem into a one-dimensional kinematic exercise, which is characteristic of introductory dynamics problems designed to reinforce the fundamental relationship between force and motion.

Furthermore, the problem specifies that the force is "constant." This detail is critical because a constant force results in a constant acceleration, according to the second law. In real-world scenarios, forces often fluctuate due to mechanical vibrations, human error, or changing environmental conditions. However, in this idealized model, the constancy of the ##20 \text{ N}## force allows us to use standard kinematic equations if we were asked to find the block's displacement or velocity at a later time. The assumption of a constant force simplifies the integration of the acceleration with respect to time, leading to a linear increase in velocity over time. This predictability is what makes Newtonian mechanics so effective for designing machinery and structural components where known loads are applied to stationary or moving parts. Accurate system identification ensures that we do not overlook any hidden variables that might affect the final outcome of the calculation.

The Significance of Frictionless Environments

One of the most important stipulations in this problem is the mention of a "smooth, frictionless" surface. Friction is a resistive force that occurs when two surfaces slide, or attempt to slide, across each other. In a typical real-world environment, a block of mass ##m## being pushed with a force ##F## would be opposed by a frictional force ##f##, where ##f = \mu F_N##, and ##\mu## is the coefficient of friction. The existence of friction would reduce the net force acting on the block to ###F_{\text{net}} = F_{\text{applied}} - f###. By stating that the surface is frictionless, the problem removes this complexity, allowing the applied force of ##20 \text{ N}## to be equal to the net force. This simplification is highly common in introductory physics as it allows the student to focus on the direct proportionality of ##F## and ##a## without the nonlinearities introduced by static and kinetic friction coefficients.

The concept of a frictionless surface is an idealization, much like the concept of a point mass or a vacuum. While no surface is truly frictionless, certain engineering applications strive to minimize friction as much as possible through the use of lubricants, ball bearings, or magnetic levitation. For instance, an air-track in a laboratory or a maglev train operates on principles that closely approximate a frictionless environment. In these cases, the efficiency of energy transfer is maximized because work done by the external force is converted entirely into kinetic energy rather than being dissipated as heat. Understanding the "frictionless" assumption helps us realize the upper limit of an object's performance; the acceleration we calculate here is the maximum possible acceleration for this block under the given force, as any amount of friction would inevitably result in a lower value.

Furthermore, the absence of friction simplifies the energy balance of the system. Without friction, there is no non-conservative work being done that would lead to a loss of mechanical energy. This means that if we were to apply the work-energy theorem, the work done by the ##20 \text{ N}## force over a distance ##d## would be exactly equal to the change in kinetic energy of the block, ###W = F \cdot d = \Delta K###. This relationship provides an alternative pathway to solving dynamics problems, though Newton’s second law remains the more direct method for finding instantaneous acceleration. By stripping away the resistive force, the problem highlights the pure relationship between force and mass. It serves as a "first principle" baseline from which more complex, realistic models involving friction, air resistance, and surface irregularities can be built and analyzed in subsequent stages of a physics or engineering curriculum.

Mathematical Execution of the Solution

Deriving Acceleration from First Principles

With the physical parameters identified and the environmental constraints understood, we can now proceed to the formal derivation of the acceleration. We begin with the vector form of Newton's second law: ###\sum \vec{F} = m \vec{a}###. As established previously, the vertical forces cancel out (##\sum F_y = 0##), and the only horizontal force is the applied force ##F##. Therefore, the net force in the x-direction is simply the applied force. We can write the scalar equation for the horizontal component as follows: ###F_x = m a_x###. In this equation, ##F_x## represents the magnitude of the horizontal force, ##m## represents the mass of the block, and ##a_x## is the resulting horizontal acceleration. The goal is to isolate the variable ##a_x## to find its value. This is achieved by dividing both sides of the equation by the mass ##m##, yielding the rearranged formula for acceleration: ###a = \frac{F}{m}###.

The process of isolating the variable is a fundamental skill in algebraic physics. It transforms a general law into a specific tool for calculation. By looking at the structure of the equation ###a = \frac{F}{m}###, we can perform a qualitative check of our expectations before plugging in the numbers. We see that if the force ##F## increases while the mass remains constant, the acceleration must increase. Conversely, if the mass ##m## increases while the force remains constant, the acceleration must decrease. This mathematical symmetry reflects the physical reality of the situation. For our block of ##5 \text{ kg}## and force of ##20 \text{ N}##, we expect a value that reflects this proportion. If we were to use a mass twice as large, say ##10 \text{ kg}##, the acceleration would be halved. This clarity of relationship is why Newtonian mechanics is considered one of the most elegant and accessible branches of theoretical physics.

It is also worth noting that because the force is constant, the acceleration remains constant throughout the duration of the force's application. This allows us to use the resulting value in kinematic equations to determine the block's motion over time. For example, if the block starts from rest (##v_0 = 0##), its velocity at any time ##t## would be given by ##v(t) = at##, and its position by ##x(t) = \frac{1}{2}at^2##. Thus, calculating the acceleration is not just an end in itself; it is the critical first step in determining the entire future state of the system. In the context of the acceleration of a block, the value we find represents the rate at which the block's velocity increases every second. Each second that the ##20 \text{ N}## force acts, the block's speed will increase by exactly the amount we are about to calculate, demonstrating the predictive power of classical dynamics.

Calculation Steps and Dimensional Analysis

We now perform the final substitution to reach the numerical answer. We are given the force ##F = 20 \text{ N}## and the mass ##m = 5 \text{ kg}##. Inserting these values into our derived equation: ###a = \frac{20 \text{ N}}{5 \text{ kg}}###. To solve this, we divide 20 by 5, which gives a numerical result of 4. However, a professional technical analysis is never complete without proper units and dimensional analysis. We must ensure that the units on both sides of the equation are consistent. As mentioned earlier, the Newton is a derived unit equal to ##\text{kg} \cdot \text{m/s}^2##. When we substitute this into our fraction, the calculation becomes: ###a = \frac{20 \text{ kg} \cdot \text{m/s}^2}{5 \text{ kg}}###. We can see that the units of kilograms in the numerator and denominator cancel out perfectly, leaving us with the units of acceleration: ##\text{m/s}^2##.

This dimensional consistency provides a "sanity check" that confirms our algebraic rearrangement was correct. If we had accidentally multiplied the force by the mass, we would have ended up with units of ##\text{kg}^2 \cdot \text{m/s}^2##, which would clearly indicate an error. The final value for the acceleration is: ###a = 4 \text{ m/s}^2###. This means that for every second the force is applied, the block's velocity increases by ##4 \text{ meters per second}##. For instance, after one second, the block would be traveling at ##4 \text{ m/s}##; after two seconds, it would reach ##8 \text{ m/s}##, and so on. This linear growth in velocity is the hallmark of motion under a constant net force. The simplicity of the final number, 4, should not overshadow the rigor of the process used to obtain it, as the same methodology applies to more complex systems in mechanical engineering and astrophysics.

In summary, the step-by-step solution involves identifying the net force, verifying the coordinate system, applying the algebraic form of Newton's second law, and conducting a final check of the units. For this easy-level problem, the steps are straightforward, but they establish the "workflow" required for advanced dynamics. Whether one is calculating the thrust needed for a satellite to change orbits or the braking force required for a high-speed train, the fundamental principle remains ###F = ma###. In our case, the smooth horizontal surface ensured that the applied force was the net force, leading to a clean and precise result of ##4 \text{ m/s}^2##. This result is robust and forms the basis for any further kinematic analysis of the block's path. By documenting the calculation with this level of detail, we ensure that the logic is transparent and the conclusion is indisputable within the framework of classical mechanics.

Engineering Applications and Synthesis

Real-World Dynamics and Machine Design

While the problem of a ##5 \text{ kg}## block on a frictionless surface may seem like a purely academic exercise, its implications are widespread in engineering and technology. The ability to calculate acceleration based on mass and force is the foundation of vehicle dynamics, aerospace engineering, and robotics. In the automotive industry, for example, engineers must determine the torque (rotational force) required from an engine to achieve a desired acceleration for a car of a specific mass. By understanding the ###F = ma### relationship, designers can optimize engine power to ensure that a vehicle can safely merge into highway traffic or carry heavy loads without sluggish performance. Even though real cars face air resistance and friction, the basic Newtonian calculation provides the initial baseline for all power-to-weight ratio assessments that define modern performance standards.

In the field of robotics and manufacturing, constant forces are often applied by hydraulic actuators or electric motors to move components along assembly lines. If a robotic arm needs to move a ##5 \text{ kg}## part with a specific acceleration to meet production timing, the control system must precisely calculate the force required to overcome the part's inertia. In high-precision environments, such as semiconductor manufacturing, the "smooth surface" idealization is closely approached through air bearings, allowing for extremely smooth and predictable motion. Engineers utilize these dynamics to minimize vibrations and ensure that delicate components are not damaged by excessive jerk (the rate of change of acceleration). Thus, the principles used to solve for our block's acceleration are the same principles that allow for the high-speed, high-precision automated world we live in today.

Furthermore, the aerospace sector relies heavily on these calculations for mission planning. When a rocket engine fires in the vacuum of space, it operates in an environment that is truly frictionless and free of air resistance, making it a perfect real-world application of the "smooth surface" model. The thrust produced by the rocket's engines acts as the constant force ##F##, and as fuel is consumed, the mass ##m## changes, leading to a varying acceleration. Even in these complex variable-mass systems, the core relationship between force, mass, and acceleration remains the governing principle. By mastering the acceleration of a block in its simplest form, students and engineers build the cognitive framework necessary to handle these advanced variables, ensuring that satellites reach their intended orbits and probes can land safely on distant planets.

Conclusion and Summary of Kinetic Principles

To conclude our analysis, we have demonstrated that a block of mass ##5 \text{ kg}## subjected to a horizontal force of ##20 \text{ N}## on a frictionless surface will experience a constant acceleration of ##4 \text{ m/s}^2##. This result was derived through a systematic application of Newton's second law, which defines the fundamental link between force and motion. We began by examining the historical context of classical mechanics, noting how the shift from Aristotelian to Newtonian thought allowed for the quantification of physical phenomena. We then identified the specific parameters of the system, noting the importance of the frictionless environment in simplifying our net force calculation. This allowed us to ignore resistive forces and focus purely on the interplay between the applied force and the block's inertia, leading to a clear mathematical path to the solution.

The calculation itself highlighted the importance of dimensional analysis and the consistency of units. By converting the force into its base units (##\text{kg} \cdot \text{m/s}^2##) and dividing by the mass in kilograms, we confirmed that our result carried the correct units for acceleration. This process ensures that the numerical answer is not just a digit, but a physical description of the block's behavior over time. The simplicity of the result, ##4 \text{ m/s}^2##, serves as a powerful reminder of the elegance of the laws of nature. It shows how complex physical interactions can be distilled into a few key variables, allowing us to predict the future state of an object with absolute certainty, provided the initial conditions are known. This predictability is the cornerstone of all scientific inquiry and technological progress, from the building of bridges to the exploration of the cosmos.

Finally, we reflected on the practical applications of this knowledge, seeing how the same logic applies to automotive safety, robotic precision, and aerospace navigation. Newton's second law is not merely a formula to be memorized for an exam; it is a universal description of the material world. Whether the system is a small wooden block in a classroom or a massive cargo ship on the ocean, the fundamental resistance of mass to a change in motion dictates how we design and interact with our environment. By thoroughly understanding the acceleration of a block, we gain a deeper appreciation for the forces that shape our reality. We hope this technical overview has provided a clear and professional insight into the mechanics of motion, reinforcing the value of classical dynamics as a vital tool for understanding the universe's mathematical harmony.

Also Read

From our network :

- Mastering DB2 12.1 Instance Design: A Technical Deep Dive into Modern Database Architecture

- AI-Powered 'Precision Diagnostic' Replaces Standard GRE Score Reports

- Mastering DB2 LUW v12 Tables: A Comprehensive Technical Guide

- Vite 6/7 'Cold Start' Regression in Massive Module Graphs

- EV 2.0: The Solid-State Battery Breakthrough and Global Factory Expansion

- 98% of Global MBA Programs Now Prefer GRE Over GMAT Focus Edition

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/analyzing-trump-deportation-numbers-insights-into-the-2026-immigration-crackdown

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/trump-political-strategy-how-geopolitical-stunts-serve-as-media-diversions

- 10 Physics Numerical Problems with Solutions for IIT JEE

RESOURCES

- Agentic CRM and ERP Solutions | Microsoft Dynamics 365

- Dynamics Inc

- Dynamics (mechanics) - Wikipedia

- DYNAMICS Definition & Meaning - Merriam-Webster

- General Dynamics | Home

- Boston Dynamics: The World's Leading Robotics Company

- Oxford Dynamics | Sonnox

- Boston Dynamics - YouTube

- Los Alamos Dynamics Summer School | Los Alamos National ...

- DYNAMICS Software - Waters | Wyatt Technology

- Jennie C. Jones: Dynamics | The Guggenheim Museums and ...

- Steel Dynamics | Steel Dynamics

- Trusted Microsoft Dynamics 365 Partner | Dynamics Square™

- Boston Dynamics CTO departs, reflects on robotics journey | Aaron ...

- Dynamics | An Open Access Journal from MDPI

0 Comments