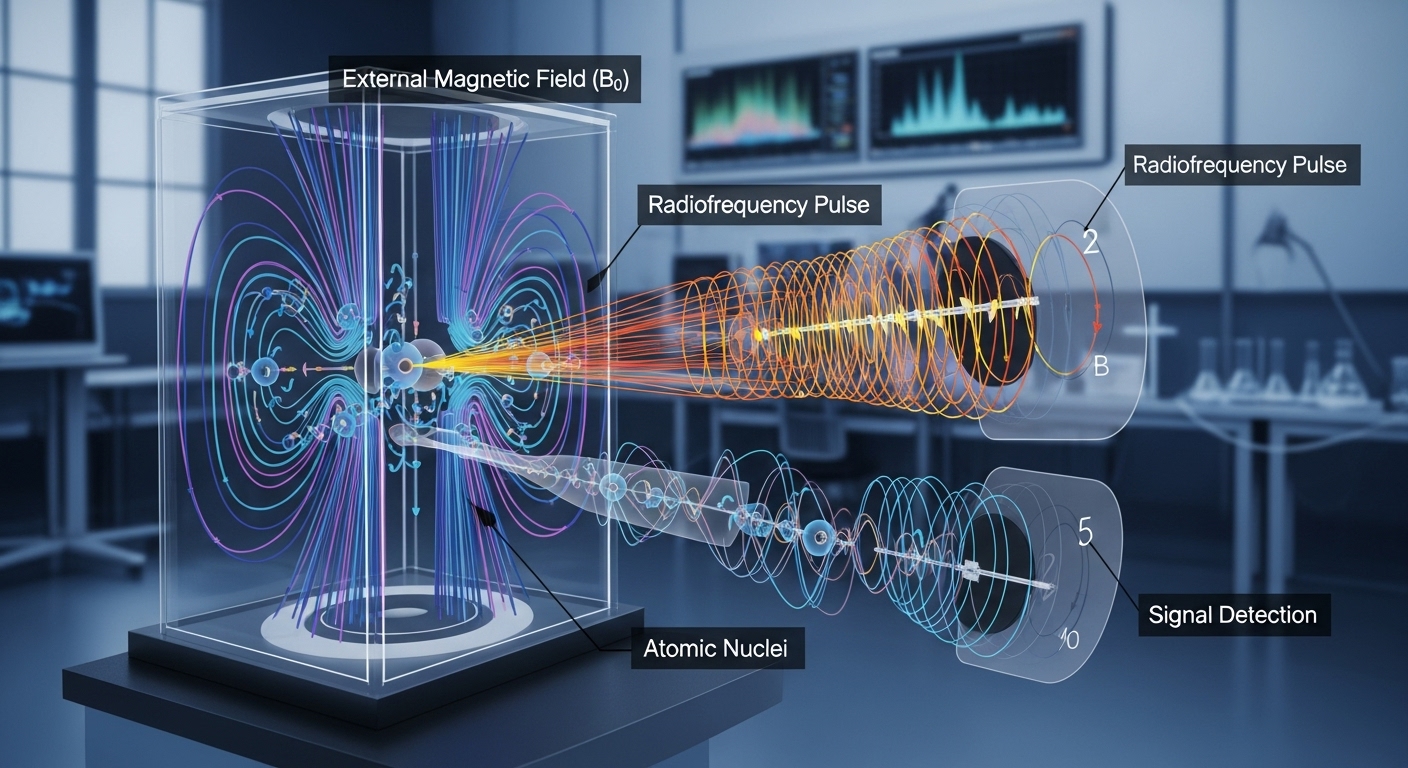

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy stands as one of the most powerful and versatile analytical techniques available to scientists today. Its profound impact spans diverse fields, from unraveling the complex structures of organic molecules and proteins to revolutionizing medical diagnostics through Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). At its core, NMR is a quantum mechanical phenomenon that exploits the magnetic properties of certain atomic nuclei when placed in a strong external magnetic field and perturbed by radiofrequency pulses. This detailed exploration will delve into the foundational principles governing NMR, the intricate processes involved, the instrumentation, and its wide-ranging applications.

On This Page

We Also Published

Fundamental Principles: Nuclear Spin and Magnetic Moment

The bedrock of NMR lies in the intrinsic property of certain atomic nuclei possessing a quantum mechanical spin angular momentum. Not all nuclei exhibit this property; it is dependent on the number of protons and neutrons within the nucleus. Nuclei with an odd number of protons, an odd number of neutrons, or both (and thus an odd mass number) possess a net nuclear spin and a non-zero magnetic moment. Examples include ## ^1\text{H} ##, ## ^{13}\text{C} ##, ## ^{15}\text{N} ##, ## ^{19}\text{F} ##, and ## ^{31}\text{P} ##, all of which are crucial in various NMR applications.

The nuclear spin quantum number, denoted as ## I ##, can take integer or half-integer values (e.g., ## I = 1/2, 1, 3/2, \dots ##). For nuclei with ## I = 0 ## (e.g., ## ^{12}\text{C} ##, ## ^{16}\text{O} ##), there is no net spin and thus no magnetic moment, rendering them NMR-inactive. The number of possible spin states for a nucleus is given by ## 2I + 1 ##, corresponding to the magnetic spin quantum numbers ## m_I ##, which range from ## -I ## to ## +I ## in integer steps.

Associated with this nuclear spin angular momentum ## \vec{I} ## is a nuclear magnetic moment ## \vec{\mu} ##. These two vectors are proportional to each other, linked by the gyromagnetic ratio ## \gamma ## (also known as magnetogyric ratio), a fundamental constant characteristic of each specific nucleus:

### \vec{\mu} = \gamma \vec{I} ###Here, ## \gamma ## is a constant that relates the magnetic moment to the angular momentum and is unique for each type of nucleus. For instance, ## ^1\text{H} ## nuclei have a large ## \gamma ## value, making them highly sensitive to NMR detection, which is why proton NMR is so prevalent. The presence of this magnetic moment means that the nucleus behaves like a tiny bar magnet. When these nuclear magnets are placed in an external magnetic field, they will tend to align themselves with or against that field, leading to distinct energy states.

The Larmor Precession

When a nucleus with a non-zero spin is placed in a static, external magnetic field, conventionally denoted as ## \vec{B_0} ##, its magnetic moment ## \vec{\mu} ## does not simply align perfectly with the field. Instead, it experiences a torque that causes it to precess around the direction of the ## \vec{B_0} ## field, similar to how a spinning top precesses in the Earth's gravitational field. This precessional motion is known as Larmor precession.

The frequency of this precession, the Larmor frequency ## \nu_L ##, is directly proportional to the strength of the applied magnetic field ## B_0 ## and the gyromagnetic ratio ## \gamma ## of the nucleus:

### \nu_L = \frac{\gamma B_0}{2\pi} ###In angular frequency units (radians per second), the Larmor frequency is ## \omega_L = \gamma B_0 ##. This equation is fundamental to understanding NMR, as it dictates the specific radiofrequency at which a particular nucleus will resonate in a given magnetic field. For example, in a ## 11.7 \text{ Tesla} ## (T) magnetic field, ## ^1\text{H} ## nuclei precess at approximately ## 500 \text{ MHz} ##, while ## ^{13}\text{C} ## nuclei precess at about ## 125 \text{ MHz} ##. This difference in Larmor frequencies allows for selective observation of different types of nuclei within a sample.

The Larmor precession is a classical analogy for a quantum mechanical phenomenon. In quantum terms, the interaction of the nuclear magnetic moment with the external magnetic field splits the degenerate nuclear spin energy levels. The energy difference between these spin states is precisely the energy required to flip the nuclear spin from one orientation to another, and this energy difference corresponds to the energy of a photon at the Larmor frequency. More details on the quantum mechanical energy states are discussed in the next section.

Interaction with an External Magnetic Field

In the absence of an external magnetic field, the ## 2I + 1 ## nuclear spin states of a nucleus are degenerate, meaning they all possess the same energy. However, when a sample containing NMR-active nuclei is placed in a strong, static external magnetic field ## \vec{B_0} ## (typically along the z-axis), the degeneracy of these spin states is lifted. This phenomenon is known as the Zeeman effect.

The energy ## E ## of a nuclear magnetic moment ## \vec{\mu} ## in a magnetic field ## \vec{B_0} ## is given by the interaction energy:

### E = - \vec{\mu} \cdot \vec{B_0} ###Since ## \vec{\mu} = \gamma \vec{I} ## and the magnetic field is along the z-axis (## \vec{B_0} = B_0 \hat{k} ##), the energy simplifies to:

### E = - \gamma B_0 I_z ###In quantum mechanics, the component of spin angular momentum along the z-axis, ## I_z ##, is quantized and can only take on values of ## m_I \hbar ##, where ## m_I ## is the magnetic spin quantum number (ranging from ## -I ## to ## +I ##) and ## \hbar ## is the reduced Planck constant. Therefore, the energy levels become:

### E = - \gamma B_0 m_I \hbar ###For a nucleus with spin ## I = 1/2 ## (e.g., ## ^1\text{H} ##, ## ^{13}\text{C} ##), there are two possible spin states: ## m_I = +1/2 ## (aligned with ## \vec{B_0} ##, lower energy, often called the ## \alpha ## spin state) and ## m_I = -1/2 ## (opposed to ## \vec{B_0} ##, higher energy, the ## \beta ## spin state).

The energy difference ## \Delta E ## between these two states is:

### \Delta E = E_{\beta} - E_{\alpha} = \left( - \gamma B_0 (-1/2) \hbar \right) - \left( - \gamma B_0 (+1/2) \hbar \right) = \gamma B_0 \hbar ###This energy difference corresponds to the energy of a photon that can induce a transition between these spin states. According to the Planck-Einstein relation (## \Delta E = h\nu ##), the frequency ## \nu ## required for resonance is:

### \nu = \frac{\Delta E}{h} = \frac{\gamma B_0 \hbar}{h} = \frac{\gamma B_0}{2\pi} ###This equation is identical to the Larmor frequency derived from classical precession. This demonstrates the seamless bridge between the classical and quantum mechanical descriptions of NMR. At thermal equilibrium, a slight excess of nuclei populates the lower energy ## \alpha ## spin state compared to the higher energy ## \beta ## spin state. This population difference is described by the Boltzmann distribution:

### \frac{N_{\alpha}}{N_{\beta}} = e^{\frac{\Delta E}{k_B T}} ###where ## N_{\alpha} ## and ## N_{\beta} ## are the populations of the lower and higher energy states, respectively, ## k_B ## is the Boltzmann constant, and ## T ## is the absolute temperature. This small but crucial population difference is what makes NMR signals detectable, as it allows for a net absorption of radiofrequency energy.

Radiofrequency Pulses and Resonance

The NMR experiment begins by placing the sample in a strong static magnetic field ## \vec{B_0} ##, establishing the Larmor precession and the Boltzmann distribution of nuclear spins. To detect an NMR signal, these equilibrium populations must be perturbed. This perturbation is achieved by applying short, intense pulses of radiofrequency (RF) electromagnetic radiation, perpendicular to the main ## \vec{B_0} ## field (typically along the x or y axis).

For a nucleus to absorb energy from this RF pulse, two conditions must be met:

- The nucleus must possess a magnetic moment (i.e., ## I \ne 0 ##).

- The frequency of the applied RF pulse must precisely match the Larmor frequency ## \nu_L ## of the nucleus in the ## \vec{B_0} ## field. This is the condition for resonance.

When the RF pulse, often referred to as ## B_1 ## field, is applied at the Larmor frequency, it causes the nuclear magnetic moments to tip away from their equilibrium alignment along the ## \vec{B_0} ## field. A common pulse used is the 90-degree pulse, which rotates the net magnetization vector from the z-axis (aligned with ## \vec{B_0} ##) into the xy-plane. Once in the xy-plane, the precessing magnetization vector induces an oscillating current in a receiver coil, which constitutes the NMR signal.

After the RF pulse is turned off, the nuclei begin to return to their equilibrium state, a process known as relaxation. As they relax, the precessing magnetization in the xy-plane decays over time, emitting a decaying sinusoidal signal. This signal, detected by the receiver coil, is called the Free Induction Decay (FID). The FID is a time-domain signal that contains all the frequency information about the resonating nuclei. To extract this frequency information, a mathematical operation called a Fourier Transform (FT) is applied to the FID, converting it from the time domain to the frequency domain, which yields the familiar NMR spectrum with distinct peaks.

The duration and amplitude of the RF pulse determine the "flip angle" of the magnetization. A 180-degree pulse, for instance, inverts the population difference, flipping the net magnetization vector from ## +z ## to ## -z ##. Advanced pulse sequences, involving multiple pulses with varying flip angles and delays, are employed in modern NMR experiments to extract highly detailed structural and dynamic information.

Relaxation Processes: T1 and T2

After excitation by an RF pulse, the nuclear spin system is not at equilibrium. It must return to its thermal equilibrium state, a process governed by relaxation mechanisms. There are two primary relaxation processes, characterized by two time constants: longitudinal relaxation (T1) and transverse relaxation (T2).

Longitudinal Relaxation (T1)

Longitudinal relaxation, or spin-lattice relaxation, describes the return of the net magnetization vector component along the ## \vec{B_0} ## field (the ## M_z ## component) to its equilibrium value. This process involves the exchange of energy between the nuclear spins and their surrounding environment, known as the "lattice." The lattice refers to all other nuclei, electrons, and molecular motions within the sample. For T1 relaxation to occur, there must be fluctuating magnetic fields at the Larmor frequency that can induce transitions between the spin states. These fluctuations are typically generated by the random molecular motions (rotations, vibrations, translations) of the surrounding molecules.

The return of ## M_z ## to equilibrium follows an exponential decay characterized by the T1 relaxation time:

### M_z(t) = M_0 (1 - e^{-t/T_1}) ###where ## M_z(t) ## is the longitudinal magnetization at time ## t ##, and ## M_0 ## is the equilibrium magnetization. T1 times can range from milliseconds to several seconds or even minutes, depending on the nucleus, molecular environment, temperature, and magnetic field strength. Longer T1 values indicate slower relaxation. T1 is crucial in determining the repetition rate of NMR experiments and is a key contrast parameter in MRI.

Transverse Relaxation (T2)

Transverse relaxation, or spin-spin relaxation, describes the loss of phase coherence of the precessing nuclear spins in the xy-plane, leading to the decay of the transverse magnetization (## M_{xy} ##). Unlike T1, T2 relaxation does not necessarily involve energy exchange with the lattice. Instead, it arises from two main factors:

- Inhomogeneities in the ## B_0 ## field: Even in a well-shimmed magnet, there are microscopic variations in the local magnetic field. Nuclei in slightly different field strengths will precess at slightly different Larmor frequencies, causing them to get out of phase with each other. This is a macroscopic effect.

- Spin-spin interactions: Each precessing nucleus generates a small local magnetic field that influences its neighbors. These fluctuating local fields cause adjacent spins to subtly dephase, contributing to T2 relaxation. This is a microscopic, inherent property of the spin system.

The decay of transverse magnetization follows an exponential decay characterized by the T2 relaxation time:

### M_{xy}(t) = M_{xy}(0) e^{-t/T_2} ###where ## M_{xy}(t) ## is the transverse magnetization at time ## t ##, and ## M_{xy}(0) ## is the initial transverse magnetization immediately after the RF pulse. T2 is always less than or equal to T1 (## T_2 \le T_1 ##). The field inhomogeneities contribute to an effective transverse relaxation time ## T_2^* ##, which is typically much shorter than the true ## T_2 ##. Techniques like spin echoes are used to remove the effects of field inhomogeneities and measure the intrinsic ## T_2 ##. T2 is critical for determining linewidths in NMR spectra and is another key contrast parameter in MRI.

The interplay of T1 and T2 relaxation mechanisms dictates the appearance of NMR signals and is meticulously studied to gain insights into molecular dynamics, structure, and interactions. Recent reports indicate the intricate dependence of these parameters on the microenvironment, offering a wealth of information about the sample's physical state. For instance, in biological systems, water molecules trapped in different cellular compartments exhibit distinct T1 and T2 values, a principle fundamental to diagnostic MRI. Detailed discussions on these processes can be found in publications by organizations like the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for biological and medical contexts.

The NMR Spectrometer

An NMR spectrometer is a complex instrument designed to generate a highly stable and homogeneous magnetic field, apply precise radiofrequency pulses, detect the weak NMR signals, and process the resulting data. The main components of a typical high-field NMR spectrometer include:

- Superconducting Magnet: This is the heart of the spectrometer, producing the strong, static ## B_0 ## magnetic field. These magnets are typically superconducting solenoids cooled by liquid helium to cryogenic temperatures (around 4 K). The strength of the magnet determines the Larmor frequency and thus the sensitivity and resolution of the spectrometer. Common field strengths for research instruments range from 7 Tesla (300 MHz for ## ^1\text{H} ##) to 23.5 Tesla (1 GHz for ## ^1\text{H} ##).

- Shim Coils: Located within the bore of the main magnet, these resistive coils generate small, localized magnetic fields that compensate for any residual inhomogeneities in the main ## B_0 ## field. Proper "shimming" is crucial for obtaining sharp, high-resolution NMR spectra.

- RF Transmitting and Receiving System: This system consists of an RF transmitter, an RF power amplifier, and a probe. The transmitter generates RF pulses at the Larmor frequency, amplified to high power levels. The probe, which contains coils, is where the sample is placed. It transmits the RF pulses and detects the weak NMR signal (FID) from the sample. Modern probes are often cryogenically cooled (cryoprobes) to significantly improve sensitivity by reducing thermal noise.

- Console (Spectrometer Electronics): This houses the intricate electronics for generating and controlling the RF pulses, digitizing the FID signal, and performing initial signal processing. It includes frequency synthesizers, pulse programmers, analog-to-digital converters (ADCs), and preamplifiers.

- Computer System: A dedicated computer controls all aspects of the spectrometer operation, from setting experimental parameters and acquiring data to performing Fourier transforms and displaying the resulting NMR spectra. It also manages data storage and analysis software.

- Sample Changer: For high-throughput applications, automated sample changers allow for unattended acquisition of multiple samples.

The entire system is designed to minimize noise and maximize signal detection, allowing for the precise measurement of subtle differences in nuclear environments. The development of more powerful magnets and sophisticated electronics has continually pushed the boundaries of NMR, enabling the study of increasingly complex systems. Advances in NMR instrumentation are routinely published by leading scientific organizations, such as the American Physical Society (APS), highlighting breakthroughs in sensitivity and resolution.

Chemical Shift

While the Larmor frequency equation ## \nu_L = \frac{\gamma B_0}{2\pi} ## suggests that all nuclei of the same type (e.g., all ## ^1\text{H} ## nuclei) should resonate at exactly the same frequency in a given ## B_0 ## field, this is not observed in practice. The most powerful aspect of NMR spectroscopy for structural elucidation is the "chemical shift."

The chemical shift arises because the local magnetic field experienced by a nucleus is not precisely equal to the applied external field ## B_0 ##. The electrons surrounding the nucleus generate their own tiny magnetic fields. These induced fields oppose the external field, effectively "shielding" the nucleus from the full strength of ## B_0 ##. The extent of this shielding depends on the electron density around the nucleus, which in turn is influenced by the chemical environment (e.g., bonding partners, electronegativity of adjacent atoms, presence of ## \pi ## systems).

The effective magnetic field ## B_{eff} ## experienced by a nucleus is:

### B_{eff} = B_0 (1 - \sigma) ###where ## \sigma ## is the shielding constant, a dimensionless quantity. Different chemical environments lead to different ## \sigma ## values, and thus different ## B_{eff} ## values, resulting in slightly different Larmor frequencies for chemically non-equivalent nuclei of the same type. This phenomenon allows NMR to differentiate between distinct atoms within a molecule.

Since the absolute resonance frequency depends on the spectrometer's ## B_0 ## field, chemical shifts are expressed on a standardized, field-independent scale, the delta (## \delta ##) scale, measured in parts per million (ppm). This is done by referencing the observed frequency to a standard reference compound (e.g., Tetramethylsilane, TMS, for ## ^1\text{H} ## and ## ^{13}\text{C} ## NMR):

### \delta = \frac{\nu_{sample} - \nu_{ref}}{\nu_{ref}} \times 10^6 \text{ ppm} ###where ## \nu_{sample} ## is the resonance frequency of the nucleus in the sample, and ## \nu_{ref} ## is the resonance frequency of the reference compound. Nuclei that are more shielded (higher electron density) resonate at lower frequencies (upfield, smaller ## \delta ## values), while those that are deshielded (lower electron density) resonate at higher frequencies (downfield, larger ## \delta ## values). Electronegative atoms (like oxygen or halogens) withdraw electron density, deshielding adjacent nuclei and shifting their signals downfield. Conversely, electron-donating groups increase shielding, shifting signals upfield.

Chemical shift values are highly characteristic and provide invaluable information about the electronic environment and functional groups present in a molecule. Comprehensive tables of chemical shift ranges exist for various nuclei in different chemical environments, aiding in structural elucidation. The understanding of chemical shifts is a cornerstone of analytical chemistry and is a topic often detailed by organizations such as the American Chemical Society (ACS).

Spin-Spin Coupling (J-Coupling)

Beyond chemical shift, another crucial source of structural information in NMR spectra is spin-spin coupling, also known as J-coupling. This phenomenon arises from the magnetic interaction between the nuclear spins of two or more chemically non-equivalent nuclei, transmitted through the bonding electrons between them.

The local magnetic field experienced by a nucleus is not only affected by its own surrounding electron cloud but also by the spin states of nearby NMR-active nuclei. The spin of one nucleus can influence the electron spins in the bonding orbital, which in turn influences the spin of a neighboring nucleus. This interaction results in the splitting of NMR signals into multiple peaks (multiplets), providing direct information about the connectivity and spatial proximity of nuclei within a molecule.

The extent of this interaction is quantified by the coupling constant, ## J ##, measured in Hertz (Hz). Unlike chemical shift, ## J ## is independent of the external magnetic field strength. The splitting pattern observed for a particular nucleus depends on the number of equivalent neighboring nuclei with which it is coupled, according to the ## (n+1) ## rule (for spin ## I=1/2 ## nuclei in a first-order spectrum). If a nucleus is coupled to ## n ## equivalent neighboring nuclei, its signal will be split into ## n+1 ## peaks. For example:

- If ## n=0 ## (no neighbors), a singlet is observed.

- If ## n=1 ## (one neighbor), a doublet is observed (two peaks).

- If ## n=2 ## (two equivalent neighbors), a triplet is observed (three peaks).

- If ## n=3 ## (three equivalent neighbors), a quartet is observed (four peaks).

The relative intensities of the peaks within a multiplet often follow Pascal's triangle (e.g., 1:1 for a doublet, 1:2:1 for a triplet, 1:3:3:1 for a quartet), reflecting the statistical probabilities of the different spin orientations of the coupled nuclei.

J-coupling provides critical information on:

- Connectivity: Which nuclei are bonded to or are near each other.

- Number of Neighbors: The ## (n+1) ## rule directly indicates the number of coupled equivalent neighbors.

- Dihedral Angles: For vicinal couplings (over three bonds, ## ^3J ##), the Karplus equation relates the coupling constant to the dihedral angle between the coupled nuclei, offering insights into molecular conformation.

- Bonding Information: Coupling constants can reveal details about bond order and hybridization.

It is important to note that the ## (n+1) ## rule applies strictly to "first-order" spectra, where the chemical shift difference between coupled nuclei (in Hz) is much larger than their coupling constant (## \Delta\nu \gg J ##). When ## \Delta\nu \approx J ##, "second-order" effects become significant, leading to more complex, distorted splitting patterns that require more advanced analysis. The study of J-coupling is a sophisticated area of NMR, frequently explored in advanced chemistry courses and research at institutions such as Stanford University.

Applications of NMR Spectroscopy

The unique insights provided by chemical shifts, spin-spin couplings, and relaxation parameters make NMR spectroscopy an indispensable tool across a vast array of scientific disciplines.

1. Structural Elucidation in Chemistry

NMR is the primary technique for determining the precise atomic structure of organic molecules, polymers, and biomolecules in solution. By combining information from ## ^1\text{H} ## NMR (number of protons, their chemical environment, and their connectivity) and ## ^{13}\text{C} ## NMR (number of unique carbon atoms, their hybridization, and functional groups), along with other heteroatom NMR (e.g., ## ^{31}\text{P} ##, ## ^{19}\text{F} ##), chemists can piece together complex molecular structures with high confidence. Advanced 2D and 3D NMR experiments, such as COSY (Correlation Spectroscopy), HSQC (Heteronuclear Single Quantum Coherence), HMBC (Heteronuclear Multiple Bond Correlation), and NOESY (Nuclear Overhauser Effect Spectroscopy), provide correlations between nuclei that are either scalar-coupled or spatially proximate, greatly simplifying structural assignments.

2. Drug Discovery and Development

In the pharmaceutical industry, NMR plays a critical role at every stage of drug discovery. It is used to characterize newly synthesized compounds, confirm the structure of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs), identify impurities, study ligand-protein interactions, determine binding affinities, and investigate molecular dynamics important for drug efficacy. Fragment-based drug discovery heavily relies on NMR screening to identify small molecules that bind to target proteins.

3. Materials Science

Solid-state NMR (SSNMR) extends the capabilities of NMR to solid materials, polymers, glasses, and catalysts. Techniques like Magic Angle Spinning (MAS) reduce anisotropic interactions, allowing for high-resolution spectra of solids. SSNMR provides insights into polymer morphology, crystallinity, local atomic order, dynamics within solids, and the structure of active sites in heterogeneous catalysts.

4. Biochemistry and Structural Biology

NMR is a powerful technique for studying the three-dimensional structures and dynamics of proteins, nucleic acids, and carbohydrates in solution. It can determine protein folding, characterize protein-ligand and protein-protein interactions, map binding sites, and study conformational changes. Unlike X-ray crystallography, NMR provides dynamic information and can analyze molecules in conditions closer to their physiological environment. For large biomolecules, isotope labeling (e.g., with ## ^{15}\text{N} ## and ## ^{13}\text{C} ##) is essential to simplify complex spectra and enable multidimensional experiments.

5. Medical Diagnostics (Magnetic Resonance Imaging - MRI)

Perhaps the most widely recognized application of NMR is Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI). MRI exploits the same fundamental principles of nuclear magnetic resonance, but instead of producing a spectrum, it generates detailed images of organs, soft tissues, bone, and virtually all other internal body structures. By varying the magnetic field linearly across the patient's body (using gradient coils), specific regions can be made to resonate at distinct frequencies. The differences in T1 and T2 relaxation times of water protons in different tissues provide the contrast needed to differentiate between healthy and diseased tissues (e.g., tumors, inflammation, demyelination in neurological disorders). MRI is non-invasive and does not use ionizing radiation, making it a safe and invaluable diagnostic tool. Its foundational principles and extensive applications are often reviewed by medical technology experts, for example, at institutions like the Harvard Medical School.

6. Food Science and Agriculture

NMR is used for quality control, authentication, and compositional analysis of food products. It can detect adulterants, determine fat and sugar content, analyze metabolite profiles, and study food deterioration processes. In agriculture, it can assess plant metabolism and soil composition.

7. Process Monitoring and Reaction Kinetics

Real-time NMR allows for monitoring chemical reactions as they occur, providing insights into reaction mechanisms, kinetics, and intermediates. This is particularly valuable in industrial chemistry for process optimization and control.

The continuous development of new NMR pulse sequences, higher field magnets, and computational tools ensures that NMR spectroscopy remains at the forefront of scientific discovery, constantly expanding its capabilities and applications.

Conclusion

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance is a sophisticated analytical technique rooted in the quantum mechanical properties of atomic nuclei. From the fundamental concepts of nuclear spin and Larmor precession to the intricate details of chemical shift, spin-spin coupling, and relaxation processes, NMR provides an unparalleled window into the atomic and molecular world. Its ability to non-invasively probe molecular structure, dynamics, and interactions has made it indispensable in fields ranging from synthetic chemistry and structural biology to materials science and clinical medicine. As technology advances, the sensitivity, resolution, and versatility of NMR continue to improve, promising even more profound discoveries and applications in the future, further solidifying its position as a cornerstone of modern science.

Also Read

RESOURCES

- Physics - Wikipedia

- American Institute of Physics

- Physics - spotlighting exceptional research

- Institute of Physics - For physics • For physicists • For all : Institute of ...

- Physics | Definition, Types, Topics, Importance, & Facts | Britannica

- Physics World: Home

- MIT Physics

- Physics

- Physics archive | Science | Khan Academy

- Department of Physics | Eberly College of Science

- Physics Today

- Physics | Illinois: Illinois Physics | The Grainger College of ...

- The Physics Classroom

- Department of Physics | The University of Chicago

- Physics Education - IOPscience

2 Comments