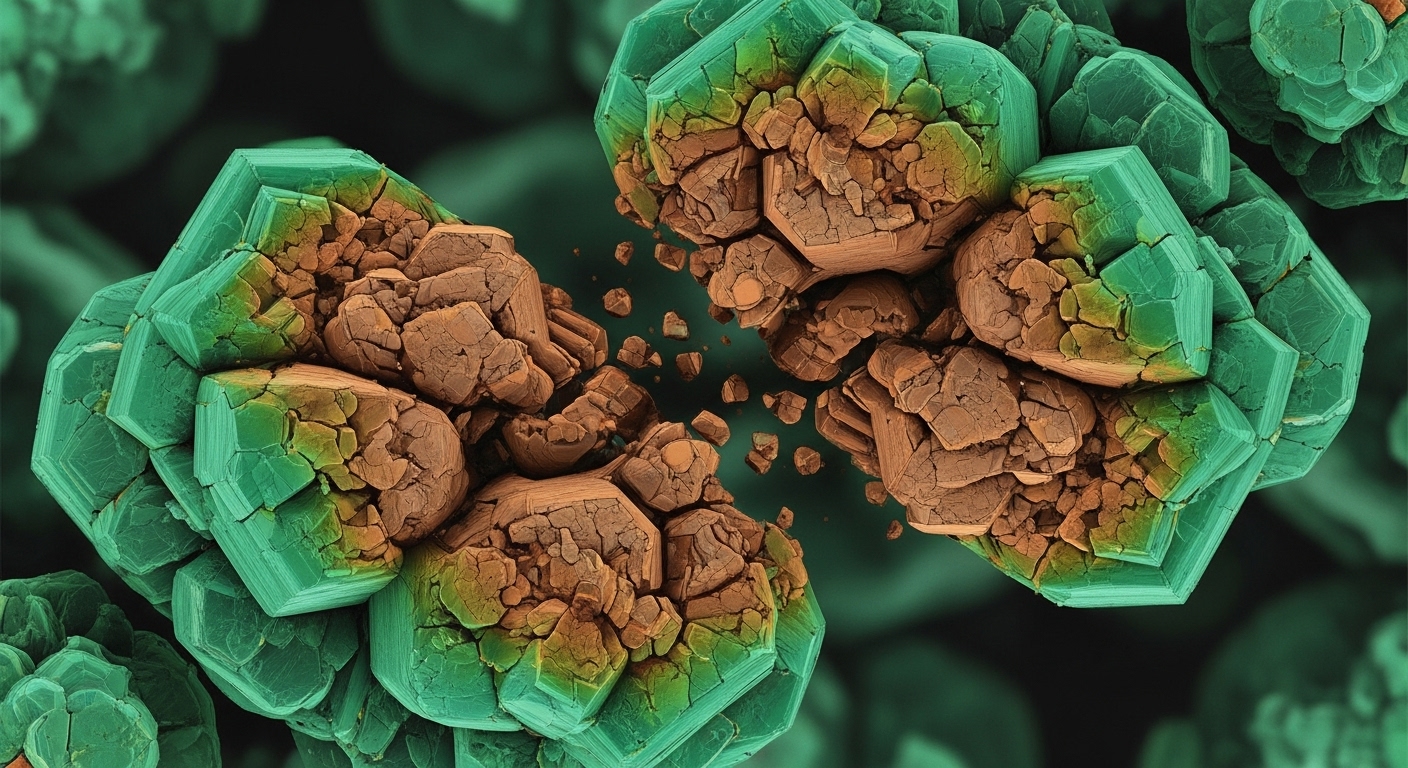

The persistence of color in cultural heritage artifacts is a subject that bridges the gap between aesthetic appreciation and rigorous materials science. Among the myriad pigments developed during the 19th century, Emerald Green—chemically known as copper acetoarsenite—stands out not only for its vibrant hue but also for its notorious instability. Historical masterpieces by artists such as Cézanne and Monet have shown signs of this chromatic deterioration, where lush greens transform into dull browns or blacks over decades. Understanding the physicochemical mechanisms driving this degradation requires a multi-disciplinary approach involving inorganic chemistry, thermodynamics, and solid-state physics.

On This Page

- 1. The Chemical Architecture of Copper Acetoarsenite

- 2. Thermodynamics of Pigment Stability

- 3. Mechanisms of Chromatic Alteration: The Role of Oxidation

- 4. Photo-Physics and Quantum Yields

- 5. The Influence of Humidity and Moisture Transport

- 6. Analytical Techniques: X-Ray Diffraction and Spectroscopy

- 7. Chemical Kinetics and Arrhenius Behavior

- 8. The Impact of Atmospheric Pollutants

- 9. Conservation Strategies and Material Science

- 10. Conclusion

We Also Published

Recent investigations into the structural integrity of synthetic emerald green have illuminated the complex pathways through which these pigments breakdown. By employing advanced spectroscopic techniques and kinetic modeling, researchers can now quantify the environmental and intrinsic factors that compromise the stability of the crystal lattice. This article provides a comprehensive technical analysis of these phenomena, exploring the stoichiometry of degradation, the influence of relative humidity, and the thermodynamic principles governing the pigment's phase transitions.

1. The Chemical Architecture of Copper Acetoarsenite

To comprehend the degradation process, one must first understand the synthesis and molecular structure of the pigment. Emerald Green, or Schweinfurt Green, is an acetate-arsenite complex of copper. Its idealized chemical formula is represented as:

### \text{Cu(CH}_3\text{COO})_2 \cdot 3\text{Cu(AsO}_2)_2 ###The synthesis traditionally involves the reaction of copper(II) acetate with arsenic trioxide (## \text{As}_2\text{O}_3 ##) in a boiling solution. The resulting precipitate crystallizes into a structure where copper ions are coordinated by acetate and arsenite ligands. The vivid green color arises from the specific d-orbital splitting of the ## \text{Cu}^{2+} ## ion in this ligand field. Copper(II) is a ## d^9 ## system, and the transitions between the split d-orbitals absorb light in the red and blue regions of the spectrum, transmitting the characteristic green wavelengths.

The stability of this complex is relatively low compared to earth pigments like ochres. The bond energies between the central copper ion and the arsenite groups are susceptible to hydrolysis and ligand exchange, particularly in the presence of acidic environments or high moisture content. The crystal lattice, while visually striking, is thermodynamically metastable, meaning that over long geological (or even historical) timescales, it tends to revert to more stable oxides and hydroxides.

From a crystallographic perspective, copper acetoarsenite forms a lattice where the acetate groups bridge copper centers, creating a polymeric network. However, the presence of the toxic arsenite group introduces a point of chemical vulnerability. Arsenic in the +3 oxidation state (## \text{As}^{3+} ##) is capable of migrating under certain conditions, a phenomenon that is central to the darkening mechanism.

2. Thermodynamics of Pigment Stability

The degradation of a chemical compound is fundamentally a thermodynamic process driven by the minimization of Gibbs Free Energy (## G ##). For the degradation reaction to proceed spontaneously, the change in Gibbs Free Energy (## \Delta G ##) must be negative. The relationship is governed by the standard equation:

### \Delta G = \Delta H - T\Delta S ###Where:

- ## \Delta G ## is the change in Gibbs Free Energy.

- ## \Delta H ## is the change in enthalpy (heat content).

- ## T ## is the absolute temperature in Kelvin.

- ## \Delta S ## is the change in entropy (disorder).

In the case of Emerald Green, the intact pigment represents a state of relatively high enthalpy compared to its decomposition products, which include copper oxides (## \text{CuO} ##, ## \text{Cu}_2\text{O} ##) and arsenic oxides (## \text{As}_2\text{O}_3 ##). The entropy term, ## T\Delta S ##, often favors decomposition because the breakdown products, especially if gaseous or smaller molecular units are released, possess higher distinct degrees of freedom.

However, the reaction is not immediate due to kinetic barriers. The activation energy (## E_a ##) required to break the copper-arsenite bonds is sufficiently high to maintain stability under controlled museum conditions. Yet, when environmental catalysts—such as photons (light energy) or moisture—are introduced, the effective activation barrier is lowered, or the system is provided with enough energy to overcome it. This thermodynamic drive suggests that the darkening of Emerald Green is an inevitability given infinite time, but the rate is determined by environmental variables.

3. Mechanisms of Chromatic Alteration: The Role of Oxidation

The primary visual evidence of degradation is the shift from green to brown or black. This color change is chemically attributed to the alteration of the copper coordination sphere and the oxidation state of the arsenic. Analytical studies utilizing X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) have detected significant shifts in the binding energies of the surface atoms of aged samples.

One prevalent mechanism is the hydrolysis of the acetate groups followed by the oxidation of the copper. While ## \text{Cu}^{2+} ## in the acetoarsenite complex is green, Copper(II) Oxide (## \text{CuO} ##) is black. If the complex breaks down effectively, ## \text{CuO} ## precipitates on the surface of the pigment particles, obscuring the green color beneath. The simplified reaction pathway can be conceptualized as:

### \text{Cu(CH}_3\text{COO})_2 \cdot 3\text{Cu(AsO}_2)_2 + H_2O \xrightarrow{h\nu, \text{O}_2} 4\text{CuO} + 3\text{As}_2\text{O}_3 + 2\text{CH}_3\text{COOH} ###This equation, while idealized, highlights the production of acetic acid (## \text{CH}_3\text{COOH} ##) and arsenic trioxide. The release of acetic acid can further catalyze the reaction by creating a localized acidic environment, which is known to accelerate the hydrolysis of ester/salt linkages. Additionally, the formation of ## \text{As}_2\text{O}_3 ## (arsenolite) has been confirmed in degraded samples. Arsenolite is white, but its presence signals the collapse of the original emerald green lattice.

More recently, researchers have identified that the interface between the pigment and the oil binder (often linseed oil) plays a critical role. The fatty acids in the oil can react with the copper ions to form copper soaps (copper carboxylates), which are often transparent green or blue-green but can disrupt the optical properties of the paint film. However, the darkening is predominantly linked to the formation of copper oxides and sulfides (if atmospheric sulfur is present).

4. Photo-Physics and Quantum Yields

Light is a potent catalyst in the degradation of inorganic pigments. The absorption of a photon by the copper complex promotes an electron from a lower energy d-orbital to a higher energy d-orbital (d-d transition) or, more destructively, facilitates a charge transfer transition. Ligand-to-Metal Charge Transfer (LMCT) bands in copper complexes are high-energy transitions, often in the UV region.

The energy of a photon is given by:

### E = h\nu = \frac{hc}{\lambda} ###Where ## h ## is Planck's constant (## 6.626 \times 10^{-34} \text{ J}\cdot\text{s} ##), ## c ## is the speed of light, and ## \lambda ## is the wavelength. Ultraviolet light, having a shorter wavelength (## \lambda < 400 \text{ nm} ##), carries sufficient energy to break chemical bonds. For example, the bond dissociation energy of a typical C-O or Cu-O bond may be comparable to the energy provided by UV photons.

When Emerald Green absorbs UV radiation, the excited state may not simply relax back to the ground state via thermal emission. Instead, the energy may be used to generate free radicals within the oil binder or on the pigment surface. These radicals (## R^\bullet ##, ## ROO^\bullet ##) are highly reactive species that can attack the organic acetate ligands, destabilizing the pigment structure. The quantum yield (## \Phi ##) of such photochemical reactions is defined as:

### \Phi = \frac{\text{Number of molecules decomposed}}{\text{Number of photons absorbed}} ###Even a low quantum yield can result in significant degradation over centuries of exposure to natural light in galleries. This necessitates the use of UV-filtering glass in modern conservation framing.

5. The Influence of Humidity and Moisture Transport

Recent reports indicate that moisture is perhaps the most significant accelerant in the darkening of Emerald Green. Water molecules can diffuse into the paint layer, interacting with the pigment particles. This interaction is not merely physical; it is chemical. Water acts as a ligand, potentially displacing the acetate or arsenite groups in the copper coordination sphere.

The kinetics of this moisture-induced degradation can be modeled using the principles of diffusion and reaction kinetics. The rate of reaction (## r ##) often follows a power law dependence on the concentration of water (## [H_2O] ##) and the pigment (## [P] ##):

### r = k [P]^m [H_2O]^n ###Where ## k ## is the rate constant, and ## m ## and ## n ## are the reaction orders. High relative humidity increases the effective concentration of water within the micropores of the paint. Furthermore, cyclic fluctuations in humidity cause mechanical stress—swelling and contracting of the binder—which can create micro-cracks, increasing the surface area exposed to oxygen and pollutants.

One specific degradation product identified in high-humidity environments is a distinct copper arsenate hydrate phase. The transformation involves the migration of arsenic ions out of the original crystal structure. In the presence of moisture, the semi-soluble arsenite groups dissolve and re-precipitate as arsenolite (## \text{As}_2\text{O}_3 ##) on the surface, leaving behind a copper-rich, darker residue.

6. Analytical Techniques: X-Ray Diffraction and Spectroscopy

Validating these theoretical mechanisms requires robust analytical data. Techniques such as Synchrotron Radiation X-ray Diffraction (SR-XRD) and X-ray Fluorescence (XRF) are pivotal. These methods allow scientists to probe the crystalline structure and elemental distribution without destroying the artwork.

X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) relies on the constructive interference of monochromatic X-rays scattered by the crystal lattice planes. The condition for constructive interference is given by Bragg's Law:

### n\lambda = 2d \sin \theta ###Where:

- ## n ## is an integer (order of reflection).

- ## \lambda ## is the wavelength of the incident X-rays.

- ## d ## is the interplanar spacing of the crystal lattice.

- ## \theta ## is the angle of incidence.

As the Emerald Green pigment degrades, the crystal structure changes. The characteristic ## d ##-spacing values for copper acetoarsenite disappear and are replaced by the diffraction patterns of degradation products like ## \text{As}_2\text{O}_3 ## (cubic lattice) and copper oxides. By monitoring the intensity of these diffraction peaks, conservation scientists can quantify the percentage of degradation in a sample.

Micro-Raman Spectroscopy provides complementary information regarding vibrational modes. The degradation of the acetate group results in the loss of specific C=O and C-H stretching vibrations in the Raman spectrum. Concurrently, new bands corresponding to Cu-O lattice vibrations in copper oxides appear. This "fingerprinting" allows for the mapping of degradation across the surface of a painting.

7. Chemical Kinetics and Arrhenius Behavior

Predicting the lifespan of these pigments involves kinetic analysis. By subjecting model samples to accelerated aging (elevated temperature and humidity), scientists can determine the temperature dependence of the degradation rate. This dependence typically follows the Arrhenius equation:

### k = A e^{-\frac{E_a}{RT}} ###By plotting ## \ln(k) ## against ## 1/T ##, the activation energy ## E_a ## can be extracted. A lower activation energy implies a reaction that is more sensitive to temperature and proceeds more readily at room temperature. Studies suggest that the ## E_a ## for the hydrolysis of copper acetoarsenite is lowered significantly in the presence of acidic pollutants (like sulfur dioxide, ## \text{SO}_2 ##), which were prevalent in the coal-burning era of the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Below is a Python simulation snippet that demonstrates how one might model the concentration decay of the pigment over time using first-order kinetics, adjusted for temperature variations.

import numpy as np

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# Constants

R = 8.314 # Gas constant, J/(mol K)

E_a = 50000 # Activation energy, J/mol (Hypothetical)

A = 1e5 # Pre-exponential factor, 1/year

T_museum = 293 # 20 degrees Celsius in Kelvin

T_uncontrolled = 303 # 30 degrees Celsius

def rate_constant(T):

return A * np.exp(-E_a / (R * T))

def concentration_over_time(t, k):

# First order decay: C(t) = C0 * exp(-kt)

return 100 * np.exp(-k * t)

years = np.linspace(0, 100, 200)

k_museum = rate_constant(T_museum)

k_warm = rate_constant(T_uncontrolled)

conc_museum = concentration_over_time(years, k_museum)

conc_warm = concentration_over_time(years, k_warm)

# Determining half-life

half_life_museum = np.log(2) / k_museum

print(f"Projected Half-life (Museum): {half_life_museum:.2f} years")

This code illustrates the dramatic effect temperature has on chemical stability. A small increase in average temperature can exponentially increase the rate constant ## k ##, thereby shortening the half-life of the pigment significantly.

8. The Impact of Atmospheric Pollutants

While moisture and light are intrinsic threats, atmospheric composition has played a historical role in the degradation of Emerald Green. During the industrial revolution, levels of sulfur dioxide (## \text{SO}_2 ##) and nitrogen oxides (## \text{NO}_x ##) were high. These gases react with moisture in the air to form acids (sulfuric and nitric acid), which deposit on the artwork surface.

Acid deposition facilitates the protonation of the acetate ligands:

### \text{CH}_3\text{COO}^- + \text{H}^+ \rightleftharpoons \text{CH}_3\text{COOH} ###Once protonated, the acetate leaves the coordination sphere of the copper, destabilizing the lattice. Furthermore, sulfur reacts directly with copper to form Copper Sulfide (## \text{CuS} ##), which is deeply black and extremely insoluble. The formation of ## \text{CuS} ## is irreversible and contributes significantly to the darkening of green pigments in urban environments. The chemical reaction can be summarized as:

### \text{Cu}^{2+} (aq) + \text{S}^{2-} (aq) \rightarrow \text{CuS} (s) ###Even trace amounts of hydrogen sulfide (## \text{H}_2\text{S} ##) in the air can initiate this process. Museums now employ activated carbon filters in HVAC systems specifically to scrub these pollutants and protect sensitive copper-based pigments.

9. Conservation Strategies and Material Science

The understanding of these degradation mechanisms informs modern conservation strategies. Since the breakdown involves oxidation, hydrolysis, and photochemical reactions, the primary defense is environmental control. This involves maintaining strict relative humidity (RH) levels, typically around 50% ±5%, and eliminating UV radiation.

However, once the degradation has occurred, it is often irreversible. The brown copper oxides cannot simply be "turned back" into the complex copper acetoarsenite lattice without completely repainting, which violates conservation ethics. Therefore, the focus is on stabilization—preventing further arsenic migration and copper oxidation.

Research is also being conducted into protective coatings. Nanotechnology offers potential solutions, such as superhydrophobic nanocoatings that prevent moisture from reaching the pigment surface while allowing the canvas to "breathe." These materials must be chemically inert so as not to interact with the original oil binder or the pigment itself.

Another area of study is the use of chelating agents to sequester free copper ions before they can precipitate as oxides, although this approach is risky and requires precise chemical control to avoid stripping the pigment of its metal centers.

10. Conclusion

The degradation of synthetic Emerald Green pigment is a multifaceted problem rooted in the fundamental principles of chemistry and physics. It serves as a potent reminder of the transient nature of materials we often consider permanent. Through the lens of thermodynamics, we see the inevitable drive toward more stable states; through kinetics, we understand the time scales involved; and through spectroscopy, we can witness the molecular transformations in real-time.

For the scientific community, the study of copper acetoarsenite provides valuable data on the long-term behavior of organometallic complexes in complex matrices. For the art world, it underscores the necessity of rigorous environmental control to preserve the visual history of humanity. As analytical techniques improve, our ability to model and perhaps one day arrest these decay processes will continue to evolve, ensuring that the vibrant greens of the 19th-century masters remain visible for future generations. For further reading on pigment chemistry and conservation science, reputable sources such as the American Chemical Society and the Royal Society of Chemistry provide extensive resources.

Also Read

From our network :

- Mastering DB2 LUW v12 Tables: A Comprehensive Technical Guide

- EV 2.0: The Solid-State Battery Breakthrough and Global Factory Expansion

- Mastering DB2 12.1 Instance Design: A Technical Deep Dive into Modern Database Architecture

- Vite 6/7 'Cold Start' Regression in Massive Module Graphs

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/trump-political-strategy-how-geopolitical-stunts-serve-as-media-diversions

- 98% of Global MBA Programs Now Prefer GRE Over GMAT Focus Edition

- AI-Powered 'Precision Diagnostic' Replaces Standard GRE Score Reports

- 10 Physics Numerical Problems with Solutions for IIT JEE

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/analyzing-trump-deportation-numbers-insights-into-the-2026-immigration-crackdown

RESOURCES

- Chemistry - Wikipedia

- The Royal Society of Chemistry

- Chemistry archive | Science | Khan Academy

- Chemistry | Definition, Topics, Types, History, & Facts | Britannica

- Food Chemistry | Journal | ScienceDirect.com by Elsevier

- Chemistry Surfboards | Chemistry Surfboards

- Chemistry 2e

- Chemistry | Chemistry

- Chemistry - Carnegie Mellon University - Department of Chemistry ...

- Chemistry in the DP - International Baccalaureate®

- Chemistry | An Open Access Journal from MDPI

- Department of Chemistry

- Chemistry: Best Full Service Independent Creative Agency

- Chemistry | PNNL

- Home | Department of Chemistry

0 Comments