Generative molecular design is revolutionizing chemistry by replacing slow trial-and-error methods with predictive AI simulations. This transition marks the end of the artisanal laboratory era, shifting the industry's competitive advantage toward high-quality training data. By integrating machine learning with robotic synthesis, researchers can now compress years of R&D into weeks, fundamentally altering how we discover new drugs and catalysts.

- Data-Centric Discovery: Competitive advantage shifts from human intuition to proprietary datasets and machine learning model accuracy.

- Closed-Loop Automation: AI-driven robots handle synthesis and spectral analysis without human intervention, accelerating the discovery cycle.

- Economic Transformation: R&D cycles shrink significantly, lowering the barrier for custom material design and disrupting traditional chemical roles.

On This Page

The Paradigm Shift in Chemical Discovery

Generative molecular design marks a fundamental shift in how modern scientists approach the creation of new chemical entities and industrial materials. Traditional methods relied heavily on human intuition and repetitive manual experimentation to identify viable candidates for pharmaceutical or industrial use. This manual process was often characterized by high failure rates and significant financial investment, creating a bottleneck in the development of life-saving medications and sustainable polymers.

Modern algorithms now analyze vast chemical libraries to predict molecular properties and reaction outcomes with unprecedented speed and accuracy across various sectors. This evolution signifies the transition of chemistry from a physical craft into a sophisticated, data-driven information science for the future. Consequently, the reliance on artisanal laboratory techniques is diminishing as predictive simulation becomes the primary driver of chemical innovation and industrial growth.

The strategic insight here is that chemistry is no longer just about mixing reagents; it is about managing complex biological and physical data. As computational power increases, the ability to simulate molecular interactions at the atomic level allows researchers to bypass thousands of physical tests. This shift reduces the time required to bring a new molecule from a conceptual stage to a validated, synthesizable product in the market.

Industry leaders are recognizing that the competitive edge is moving away from who has the most experienced chemists to who possesses the best data. Large-scale datasets of molecular properties and reaction conditions are becoming the most valuable assets for any chemical or pharmaceutical corporation today. The era of the "chemist's intuition" is being augmented, and in some cases replaced, by deep learning architectures and neural networks.

This death of trial-and-error synthesis does not mean the end of chemistry, but rather its rebirth as a digital-first discipline of science. By focusing on the informational aspects of molecular structure, scientists can explore a chemical space that is far too vast for human cognition. The potential for discovering entirely new classes of materials is now limited only by the quality of our training data and models.

From Artisanal Benchwork to Data-Driven Logic

The transition from manual benchwork to data-driven logic represents a move toward a more predictable and scalable model of scientific discovery and production. Historically, a chemist spent years developing a "feel" for reactions, which was difficult to document, share, or scale across different laboratories. This artisanal approach, while successful for centuries, is inherently limited by human physical capacity and the slow pace of manual labor.

Data-driven logic replaces this subjectivity with objective metrics derived from massive datasets of previous experiments, including those that were considered total failures. By training AI models on both successful and unsuccessful outcomes, researchers can identify hidden patterns that dictate whether a specific reaction will succeed. This holistic view of chemical data allows for the optimization of synthesis pathways that a human chemist might never consider.

Furthermore, the digitization of laboratory workflows ensures that every observation is recorded in a format that machine learning models can easily consume and analyze. This creates a virtuous cycle where every experiment, regardless of its outcome, improves the predictive accuracy of the generative design system. The laboratory becomes a data factory, churning out insights that refine the underlying logic of the molecular discovery process.

As these systems become more sophisticated, they can suggest novel molecular scaffolds that satisfy multiple constraints, such as toxicity, solubility, and manufacturing cost. This multi-objective optimization is a hallmark of data-driven logic, allowing for the design of molecules that are not just effective but practical. The result is a more streamlined R&D pipeline that prioritizes the most promising candidates with high statistical confidence.

Ultimately, the move away from artisanal methods allows for a democratization of chemical design, where smaller firms can compete using advanced algorithms. The barrier to entry is no longer the size of the physical laboratory but the quality of the digital infrastructure and data. This shift is leveling the playing field and accelerating the pace of innovation across the entire global chemical industry.

The Role of Information Science in Synthesis

Information science provides the theoretical framework necessary to navigate the nearly infinite dimensions of chemical space, which contains an estimated ##10^{60}## molecules. Without the tools of informatics, exploring this space is like searching for a needle in a cosmic haystack using only manual tools. Generative models act as high-resolution maps, guiding researchers toward regions of chemical space that are likely to contain molecules with desired traits.

The integration of information science into synthesis allows for the representation of molecules as complex graphs or strings that machines can manipulate. SMILES strings and molecular graphs serve as the primary languages through which AI models understand and generate new chemical structures for testing. This abstraction enables the application of powerful natural language processing and graph neural network techniques to the problems of chemical synthesis.

By treating chemistry as a branch of information science, researchers can apply principles of entropy and information theory to molecular design and optimization. This perspective helps in understanding the complexity of synthetic routes and the probability of achieving a specific molecular configuration under given conditions. The synthesis process becomes a series of logical operations performed on a digital representation of matter, rather than a mystery.

Moreover, information science facilitates the cross-disciplinary collaboration required for modern drug discovery and material science by providing a common digital language. Bioinformaticians, data scientists, and chemists can now work on the same models, each contributing their expertise to refine the generative process. This synergy is essential for tackling the complex challenges of personalized medicine and sustainable energy storage in the modern world.

As we move forward, the role of the information scientist in chemistry will continue to grow, overshadowing traditional laboratory roles in strategic importance. The ability to architect data pipelines and design robust machine learning models will be the defining skill set for future chemical engineers. The lab bench is becoming a peripheral device to the central processing unit where the real discovery happens.

Mathematical Frameworks of Molecular Generation

The mathematical foundations of generative molecular design are rooted in deep generative models that can learn the underlying distribution of chemical structures. These models allow for the sampling of new molecules that are statistically similar to known compounds but possess unique and optimized properties. Understanding these frameworks is crucial for technical professionals who wish to implement or oversee AI-driven research and development projects.

Probabilistic models, such as Variational Autoencoders and Generative Adversarial Networks, provide the structure necessary to map discrete molecular data into a continuous space. This continuous latent space allows for the use of gradient-based optimization techniques to "walk" toward more desirable molecular configurations and properties. The mathematics of these transformations ensures that the generated molecules remain chemically valid and synthesizable in a laboratory setting.

Another critical mathematical component is the use of reinforcement learning to guide the generation process toward specific target goals or performance metrics. By defining a reward function based on desired molecular properties, the model learns to prioritize the creation of molecules that maximize that reward. This approach is particularly effective for optimizing complex traits like binding affinity to a specific protein or thermal stability.

Graph theory also plays a vital role, as molecules are naturally represented as nodes and edges in a mathematical graph structure. Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) allow the model to learn spatial and connectivity patterns that are essential for predicting molecular reactivity and physical behavior. These mathematical representations capture the three-dimensional nature of chemistry far better than simple linear strings or traditional structural formulas.

Finally, Bayesian optimization is often used to manage the trade-off between exploring new chemical regions and exploiting known high-performing molecular scaffolds. This mathematical strategy ensures that the generative process is efficient, minimizing the number of expensive physical experiments required to validate the AI's predictions. The combination of these frameworks creates a powerful engine for rapid and autonomous molecular discovery and optimization.

Variational Autoencoders and Latent Space Navigation

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) are a cornerstone of generative molecular design, providing a way to compress high-dimensional chemical data into a lower-dimensional latent space. The encoder network maps a molecule to a probability distribution in the latent space, while the decoder reconstructs the molecule from a sample. This structure allows the model to learn a continuous representation of chemistry where similar molecules are located close together.

Navigating this latent space is the key to discovering novel molecules with specific properties through interpolation or targeted optimization techniques in the model. By moving along a vector in the latent space, a researcher can observe how the molecular structure changes and how those changes affect properties. This allows for a level of precision in molecular engineering that was previously impossible using traditional trial-and-error laboratory synthesis.

The objective function of a VAE involves balancing the reconstruction accuracy with the regularity of the latent space to ensure meaningful generation. This is typically achieved through a loss function that includes a Kullback-Leibler divergence term to penalize deviations from a prior distribution. The mathematical formulation of the VAE loss function for molecular generation is typically expressed as follows:

###\mathcal{L}(\theta, \phi; \mathbf{x}) = -E_{q_\phi(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x})}[\log p_\theta(\mathbf{x}|\mathbf{z})] + \beta D_{KL}(q_\phi(\mathbf{z}|\mathbf{x}) || p(\mathbf{z}))###In this equation, ##\mathbf{x}## represents the input molecular data, while ##\mathbf{z}## is the latent representation within the generative model. The parameter ##\beta## controls the weight of the KL divergence term, which is essential for ensuring the latent space remains smooth and navigable. A well-trained VAE allows for the generation of valid, diverse molecules that populate the gaps in known chemical databases.

By optimizing within this latent space, researchers can find the "sweet spot" where a molecule possesses the ideal balance of efficacy and safety. This mathematical approach to design is far more efficient than the random search or local optimization strategies used in classical medicinal chemistry. VAEs have successfully identified new drug candidates that are currently undergoing clinical trials, proving the practical utility of this framework.

Reinforcement Learning for Reaction Optimization

Reinforcement Learning (RL) provides a dynamic framework for optimizing chemical reactions by treating the synthesis process as a sequence of decision-making steps. In this context, an agent learns to select the best reagents, temperatures, and catalysts to maximize the yield or purity of a product. The agent receives feedback from either a simulator or a physical robotic lab, allowing it to improve its strategy over time.

The beauty of RL in chemistry is its ability to handle the high-dimensional and non-linear nature of chemical reaction spaces effectively. Traditional optimization methods like "one-variable-at-a-time" are notoriously inefficient and often miss complex interactions between different reaction parameters during the synthesis. RL agents can explore these interactions simultaneously, finding global optima that human researchers might overlook due to cognitive biases or limitations.

One common application of RL is in the design of synthetic routes, where the agent must find the most efficient path from precursors. This involves balancing the number of steps, the cost of materials, and the environmental impact of the chosen chemical processes. The RL agent essentially plays a game of "chemical chess," where the goal is to reach the target molecule with minimal effort.

To implement RL effectively, researchers must define clear reward functions that reflect the strategic goals of the chemical project or industrial process. These rewards can be based on real-time data from automated sensors, creating a closed-loop system where the AI learns from every reaction. This iterative learning process is what allows for the rapid optimization of synthesis conditions from months down to mere days.

As RL algorithms become more efficient, they are being integrated directly into the control systems of autonomous laboratories for real-time synthesis management. These agents can adjust reaction parameters on the fly, responding to unexpected changes in the chemical environment or equipment performance. This level of adaptive control is a critical component of the "death of trial-and-error" in modern chemical manufacturing.

We Also Published

The Architecture of Closed-Loop Autonomous Labs

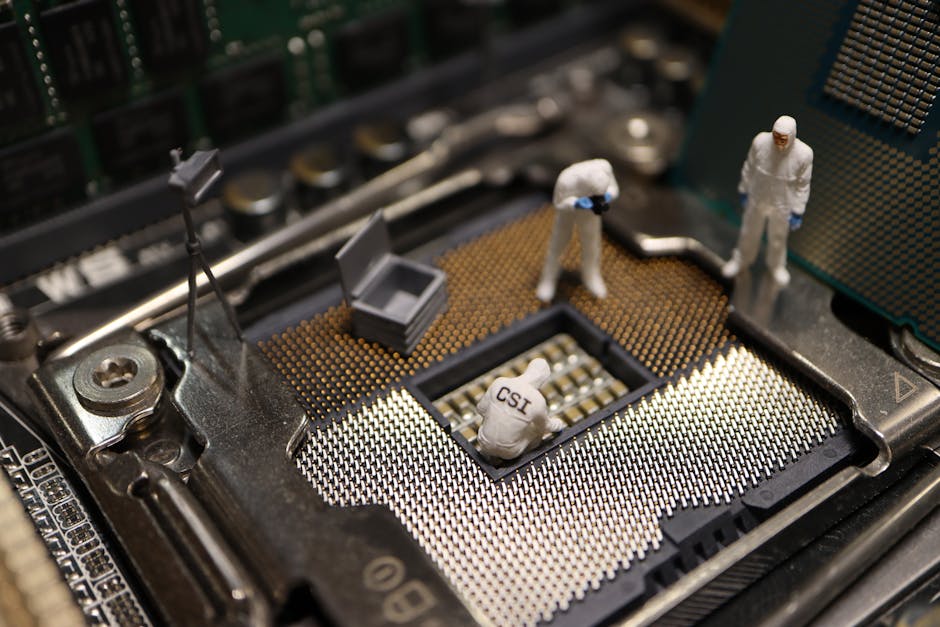

The architecture of a closed-loop autonomous lab represents the physical manifestation of the shift from artisanal work to integrated information science. These facilities combine high-throughput robotic hardware with advanced AI orchestration layers to perform experiments without the need for constant human supervision. The goal is to create a seamless pipeline where the AI designs, executes, and analyzes experiments in a continuous, self-correcting loop.

In a typical closed-loop system, the AI starts by generating a hypothesis or a specific molecular target based on existing data. This target is then translated into a series of robotic instructions that control liquid handlers, heaters, and various analytical instruments. The robot performs the synthesis, and the resulting product is automatically transferred to an integrated spectrometer for immediate characterization.

The data from the characterization step is fed back into the AI model, which compares the results with its initial predictions. If the experiment failed or produced unexpected results, the AI analyzes the spectral data to understand why and adjusts its next attempt. This "active learning" approach allows the system to converge on the correct solution much faster than a human-led experimental campaign.

The physical layout of these labs is designed for modularity and scalability, allowing for the rapid integration of new instruments or technologies. Sensors throughout the facility monitor environmental conditions and equipment health, ensuring that the data produced is consistent and high-quality for analysis. This level of environmental control is difficult to achieve in a traditional lab setting where human presence can introduce variability.

Closed-loop labs are not just faster; they are also safer and more sustainable than traditional facilities because they minimize chemical waste. By optimizing reactions in silico before performing them physically, the system only uses reagents for the most promising and viable experiments. This efficiency is crucial for the future of green chemistry and the development of sustainable industrial processes worldwide.

Integrating LLMs with Robotic Hardware Systems

Large Language Models (LLMs) are increasingly being used as the "brain" of autonomous laboratories, acting as an interface between humans and robots. These models can read scientific literature, extract experimental protocols, and translate them into machine-executable code for robotic liquid handling systems. This capability bridges the gap between the vast body of human chemical knowledge and the precision of modern robotic hardware.

By using LLMs, researchers can describe a desired synthesis in natural language, and the system will automatically generate the necessary instructions. This "Chemical Prompt Engineering" allows scientists to focus on high-level strategy rather than the minutiae of programming robotic movements or workflows. The LLM can also suggest modifications to protocols based on its extensive training on millions of published chemical reaction papers.

The integration involves sophisticated software wrappers that map the LLM's output to the specific API calls required by the laboratory hardware. This ensures that the instructions are not only chemically sound but also physically possible for the specific robots in the lab. The following Python snippet demonstrates a simplified conceptual interface for generating molecular data using a standard chemical informatics library:

from rdkit import Chem

from rdkit.Chem import AllChem

# Define a molecule from SMILES string

molecule = Chem.MolFromSmiles('CC(=O)OC1=CC=CC=C1C(=O)O')

# Generate 3D coordinates for the molecule

AllChem.EmbedMolecule(molecule)

AllChem.MMFFOptimizeMolecule(molecule)

# Calculate and print the molecular weight

print(f"Molecular Weight: {AllChem.CalcExactMolWt(molecule):.2f}")This type of programmatic control allows the AI to manipulate molecular structures and prepare them for simulation or physical synthesis. The LLM can orchestrate these scripts, calling different libraries to perform tasks like solubility prediction or toxicity screening before synthesis. This level of automation is what enables the rapid R&D cycles that are currently disrupting the pharmaceutical and materials industries.

As LLMs become more specialized in chemistry, they will be able to reason about complex reaction mechanisms and potential side reactions. This reasoning capability is essential for autonomous labs to handle the nuances of organic synthesis where subtle changes can fail. The combination of LLMs and robotics is creating a new paradigm of "self-driving" laboratories that operate around the clock.

Real-Time Spectral Analysis and Feedback Loops

Real-time spectral analysis is the sensory component of the closed-loop lab, providing the AI with immediate feedback on experimental outcomes. Instruments like NMR, IR, and Mass Spectrometers are integrated directly into the workflow, allowing for the rapid characterization of products. The AI must be able to interpret these complex signals to determine if the desired molecule was successfully synthesized.

Automated spectral interpretation is a challenging task that requires deep learning models trained on millions of simulated and experimental spectra. These models can identify functional groups, determine molecular weight, and even suggest the three-dimensional structure of the synthesized compound quickly. This automated analysis eliminates the days or weeks usually spent waiting for a core facility to process and return samples.

The feedback loop is closed when the AI uses the spectral data to update its internal model of the reaction space. If the yield was low, the AI might calculate the similarity between the intended product and the observed side products. One common metric for this is the Tanimoto similarity, which measures the overlap between two molecular fingerprints to quantify their relatedness:

###T(A, B) = \frac{N_c}{N_a + N_b - N_c}###In this formula, ##N_c## is the number of common features, while ##N_a## and ##N_b## are the features in molecules A and B. By analyzing these similarities, the AI can deduce which parts of the molecule are unstable or which reagents are failing. This mathematical insight guides the next iteration of the experiment, ensuring continuous improvement and eventual success in synthesis.

The integration of real-time analysis also allows for the detection of unstable intermediates that would be missed in manual chemistry. This provides a deeper understanding of reaction kinetics and mechanisms, leading to the discovery of more efficient and novel pathways. The lab becomes a dynamic environment where the AI and the physical world are in constant, data-rich communication with each other.

Strategic Implications for the Chemical Industry

The death of trial-and-error synthesis has profound strategic implications for the global chemical industry, affecting everything from workforce requirements to intellectual property. Companies that fail to adapt to this information-centric model risk becoming obsolete as their competitors accelerate their discovery pipelines. The strategic focus is shifting from physical infrastructure to digital maturity and the acquisition of high-quality experimental data assets.

One major implication is the dramatic reduction in the cost and time required to bring new products to the market. This allows for a more "agile" approach to chemical manufacturing, where custom materials can be designed for niche applications profitably. The ability to quickly respond to market demands or environmental regulations becomes a key competitive advantage in a rapidly changing world.

Intellectual property strategies are also evolving, as the value of a patent may depend more on the data used to discover it. Companies are increasingly protective of their training datasets and the proprietary algorithms they use to navigate the complex chemical space. This is leading to new types of data-sharing agreements and collaborations between tech companies and traditional chemical manufacturers in the industry.

The barrier to entry for custom material design is collapsing, allowing startups to challenge established giants with much smaller physical footprints. By leveraging cloud-based AI and "lab-as-a-service" providers, these small firms can conduct high-level research without massive capital expenditures. This democratization of discovery is likely to lead to a surge in innovation across the biotech and materials science sectors.

Finally, the shift toward generative design is forcing a re-evaluation of the entire chemical supply chain and production process. If molecules can be designed and synthesized autonomously, the location of manufacturing may shift closer to the point of consumption. This move toward "distributed manufacturing" could reduce transportation costs and the environmental impact of the global chemical and pharmaceutical industries.

The Value of Legacy Data and Failed Experiments

In the new era of generative molecular design, the most valuable asset a company possesses is its historical experimental data. This includes not only the successful patents but also the millions of "failed" experiments that never made it into journals. This "dark data" contains the critical information needed to teach AI models what does not work and why it fails.

Digitizing legacy data is a massive undertaking, but it is essential for building proprietary AI models that offer a competitive advantage. Companies that have decades of well-documented lab notebooks have a significant head start over newer entrants who must generate data. The ability to mine this historical data for patterns is like having a map of a territory others are exploring blindly.

Failed experiments are particularly useful for defining the boundaries of chemical reactivity and the limitations of specific catalysts or reagents. Without this negative data, AI models tend to be over-optimistic and may suggest many reactions that are physically impossible to perform. Including failures in the training set creates a more robust and realistic model of the chemical world for the AI.

The process of data curation involves cleaning, standardizing, and labeling old records to make them machine-readable and useful for training. This requires a combination of chemical expertise and data engineering skills to ensure that the context of the experiments is preserved. Once curated, this data becomes a reusable resource that can power multiple generations of molecular design and discovery models.

Strategic investment in data infrastructure is now more important than investment in new glassware or traditional laboratory equipment for many firms. The companies that successfully unlock the value of their legacy data will be the ones that lead the chemical industry. This data-first approach is the primary driver of the transition away from the artisanal lab bench era toward automation.

Future Workforce Dynamics and Chemical Prompt Engineering

The transformation of chemistry into an information science is fundamentally changing the skills required for a successful career in the industry. Traditional lab technician roles are being replaced by "Chemical Prompt Engineers" and "Digital Chemists" who bridge the gap between AI and matter. These professionals must be proficient in both organic chemistry and data science to manage the new autonomous laboratory workflows.

Chemical Prompt Engineering involves the ability to structure queries and constraints for AI models to produce the most viable molecular designs. This requires a deep understanding of chemical principles to validate the AI's suggestions and to troubleshoot the robotic synthesis processes. The focus of the chemist's work is shifting from physical execution to high-level strategic oversight and model refinement.

Education in chemistry must evolve to include training in programming, statistics, and machine learning as core components of the undergraduate curriculum. Students need to understand how to interact with digital twins and how to interpret the output of generative molecular models. The "chemical intuition" of the future will be a blend of physical understanding and algorithmic literacy for the digital age.

This shift also creates new opportunities for cross-disciplinary roles that combine chemistry with robotics, software engineering, and ethics in science. As AI takes over the routine tasks of synthesis, human researchers can focus on the more creative and ethical aspects of discovery. This includes considering the societal impact of new materials and ensuring that the AI is used in a responsible manner.

While some traditional roles may disappear, the overall demand for skilled professionals who can navigate the intersection of AI and chemistry is growing. The industry needs leaders who can manage the transition to autonomous labs and who can leverage data to solve global challenges. The chemist of 2026 is a data scientist who understands the language of molecules and the power of AI.

Also Read

From our network :

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/analyzing-trump-deportation-numbers-insights-into-the-2026-immigration-crackdown

- Mastering DB2 12.1 Instance Design: A Technical Deep Dive into Modern Database Architecture

- AI-Powered 'Precision Diagnostic' Replaces Standard GRE Score Reports

- Vite 6/7 'Cold Start' Regression in Massive Module Graphs

- Mastering DB2 LUW v12 Tables: A Comprehensive Technical Guide

- EV 2.0: The Solid-State Battery Breakthrough and Global Factory Expansion

- 98% of Global MBA Programs Now Prefer GRE Over GMAT Focus Edition

- 10 Physics Numerical Problems with Solutions for IIT JEE

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/trump-political-strategy-how-geopolitical-stunts-serve-as-media-diversions

RESOURCES

- Machine learning-aided generative molecular design - Nature

- Generative Molecular Design Isn't As Easy As People Make It Look

- Deep generative molecular design reshapes drug discovery - PubMed

- Review Deep generative molecular design reshapes drug discovery

- Augmented Memory: Sample-Efficient Generative Molecular Design ...

- Generative models for molecular discovery: Recent advances and ...

- Saturn: Sample-efficient Generative Molecular Design using ... - arXiv

- Deep generative molecular design reshapes drug discovery - PMC

- [2505.08774] Generative Molecular Design with Steerable and ...

- Inverse molecular design using machine learning - Science

- Directly optimizing for synthesizability in generative molecular ...

- (PDF) Machine learning-aided generative molecular design

- Multimodal Bonds Reconstruction Towards Generative Molecular ...

- Molecular design in drug discovery: a comprehensive review of ...

- Synthesizability via Reward Engineering: Expanding Generative ...

0 Comments