In the vast landscape of energy conversion technologies, engines that harness thermal energy to produce mechanical work stand as pillars of modern civilization. Among these, external combustion engines (ECEs) occupy a distinct and historically significant position. Unlike their internal combustion counterparts, where fuel ignites within the working fluid, ECEs separate the combustion process from the working fluid, employing an external heat source to drive a thermodynamic cycle. This fundamental distinction imbues ECEs with unique characteristics, advantages, and engineering complexities that merit a thorough scientific and mathematical examination.

On This Page

- The Enduring Legacy of External Heat Transformation

- Fundamental Principles Governing Heat Engine Operation

- Architectural Divergence: External vs. Internal Combustion

- The Stirling Engine: A Paragon of Regenerative Thermal Cycles

- Rankine Cycle Systems: The Dominance of Steam Power

- Exploring Other External Combustion Engine Architectures

- Thermodynamic Limitations and Practical Efficiency Considerations

- Engineering Challenges in System Design and Optimization

- Environmental Implications and the Path to Sustainable Power

- The Evolving Horizon of External Thermal Machines

We Also Published

The Enduring Legacy of External Heat Transformation

The journey of external combustion engines began with the pioneering work on steam power, fundamentally altering industrial capabilities and transportation during the Industrial Revolution. From the atmospheric engine of Thomas Newcomen to James Watt's vastly improved designs, and later to the sophisticated steam turbines, the principle remained consistent: an external fire heats water to produce steam, which then expands to do work. While internal combustion engines (ICEs) later dominated automotive and aviation sectors due to their power-to-weight ratio and fuel flexibility, ECEs, particularly in the form of steam turbines, remain the bedrock of global electricity generation, often operating on the Rankine cycle. Beyond steam, the ingenious Stirling engine, conceived in the early 19th century, offered another elegant solution for external heat conversion, promising quieter operation and cleaner emissions, though facing its own set of engineering hurdles. Understanding these machines requires a deep dive into the foundational principles of thermodynamics, material science, and fluid dynamics.

Fundamental Principles Governing Heat Engine Operation

At their core, all heat engines operate on the same fundamental principles derived from the laws of thermodynamics. The First Law, a statement of energy conservation, asserts that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed. For a thermodynamic cycle, this means the net heat added to the system equals the net work done by the system: ### Q_{net} = W_{net} ### where ## Q_{net} ## is the net heat transferred to the working fluid and ## W_{net} ## is the net work done by the engine. The Second Law of Thermodynamics, however, introduces the crucial concept of entropy and dictates that no heat engine can convert all heat supplied to it into useful work. This law sets an upper limit on the efficiency of any heat engine operating between two temperature reservoirs.

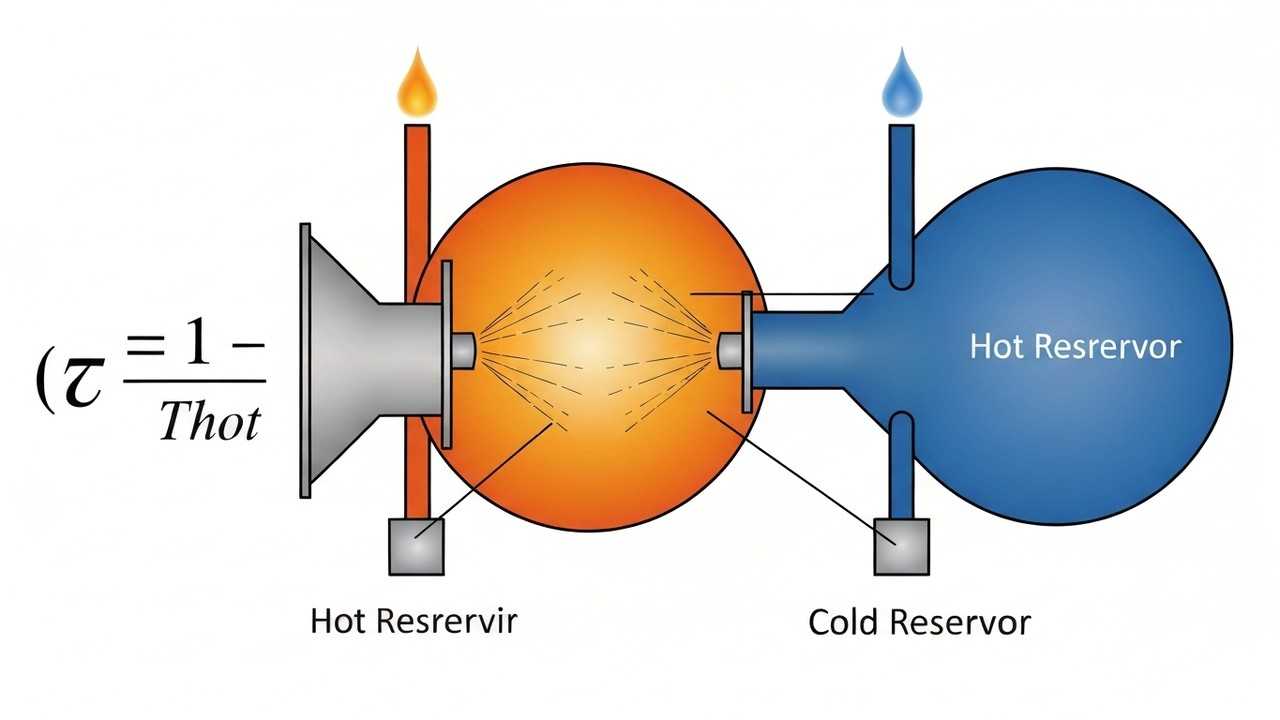

The theoretical maximum efficiency is achieved by the ideal Carnot cycle, which postulates a reversible process between a high-temperature heat source (## T_H ##) and a low-temperature heat sink (## T_C ##). Its efficiency, ## \eta_C ##, is given by:

### \eta_C = 1 - \frac{T_C}{T_H} ###where temperatures ## T_H ## and ## T_C ## are absolute temperatures (e.g., Kelvin). This equation highlights a critical design objective for ECEs: to operate with the largest possible temperature difference between the heat source and sink. Practical engines, however, are irreversible and thus cannot achieve Carnot efficiency. Irreversibilities arise from factors such as friction, finite heat transfer rates, and throttling losses. These factors necessitate a more detailed analysis of specific thermodynamic cycles, such as the Rankine and Stirling cycles, which form the basis for most ECE designs. For more information on the foundational principles of thermodynamics, reputable resources such as those provided by the U.S. Department of Energy offer comprehensive insights.

Architectural Divergence: External vs. Internal Combustion

The defining characteristic of an external combustion engine is the spatial and temporal separation of the combustion process from the working fluid that drives the mechanical output. In an ECE, fuel is burned in an external furnace or combustor, and the heat generated is transferred through a heat exchanger to the working fluid, which then expands to perform work. Examples include steam engines, Stirling engines, and external combustion gas turbines.

In contrast, an internal combustion engine (ICE) combusts fuel directly within the engine's working chamber, typically a cylinder, where the expanding hot gases directly push a piston. Gasoline and diesel engines are prime examples. This distinction leads to several key differences:

- Working Fluid Contamination: ECEs typically use a clean, sealed working fluid (e.g., water/steam, air, helium, hydrogen), which does not come into direct contact with combustion products. This reduces wear and tear, prolongs engine life, and minimizes internal fouling. ICEs, however, expose their working fluid (air/fuel mixture) directly to combustion, leading to soot, carbon deposits, and corrosive byproducts.

- Fuel Flexibility: The external nature of combustion in ECEs allows for immense fuel flexibility. They can be powered by almost any heat source, including solid fuels (coal, biomass), liquid fuels, gaseous fuels, solar thermal energy, geothermal heat, and even nuclear fission. ICEs, by design, are more limited to specific types of refined liquid or gaseous fuels.

- Combustion Control and Emissions: External combustion allows for more controlled and continuous combustion processes, which can lead to more complete combustion and potentially lower emissions of pollutants like nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter. Exhaust gas recirculation (EGR) and other emission control strategies are more easily integrated due to the steady-state nature of the heat source.

- Operating Pressure and Temperature: The peak pressures and temperatures in ECEs occur in the heat exchanger and working fluid loop, which are designed to handle these conditions. In ICEs, these peaks occur transiently within the combustion chamber, necessitating robust engine block and piston designs.

- Power Density and Start-up Time: Generally, ICEs offer higher power density (power per unit mass or volume) and faster start-up times dueaking them suitable for mobile applications. ECEs, especially steam systems, often have lower power densities and require significant warm-up periods to build pressure and temperature. However, for continuous power generation, their stability and fuel flexibility often outweigh these considerations.

The choice between an ECE and an ICE architecture hinges on the specific application, available fuel sources, emission targets, and operational requirements. Further exploration of engine design and operation can be found through academic institutions like those documented by the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

The Stirling Engine: A Paragon of Regenerative Thermal Cycles

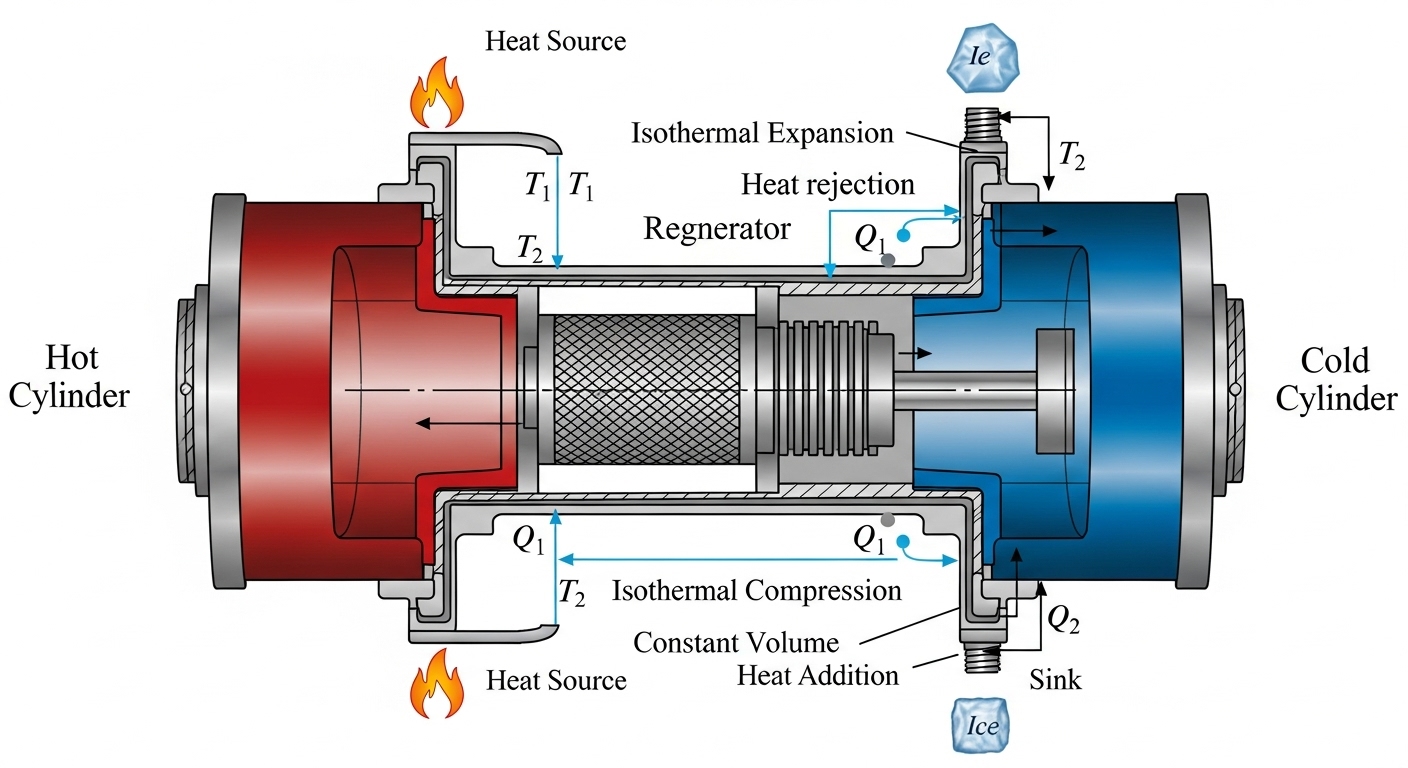

Conceived by Robert Stirling in 1816, the Stirling engine is a fascinating example of an external combustion engine that operates on a closed regenerative thermodynamic cycle. Its defining feature is the use of a regenerator, a device that stores and releases heat during the cycle, significantly improving thermal efficiency. The ideal Stirling cycle consists of four reversible processes:

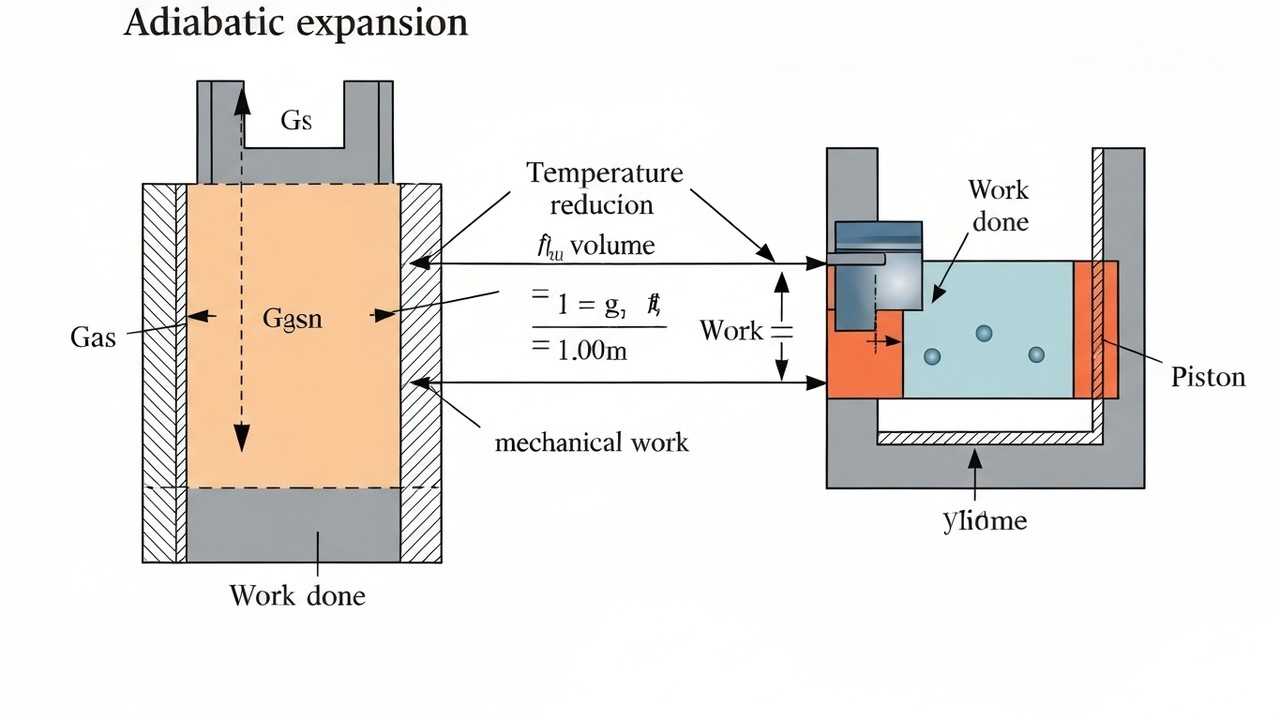

- Isothermal Expansion (1-2): The working fluid (e.g., air, helium, hydrogen) expands isothermally at the high temperature ## T_H ##, absorbing heat ## Q_H ## from the external heat source. During this phase, work ## W_{12} ## is done by the fluid. For an ideal gas, the heat absorbed is equal to the work done: ### Q_{12} = W_{12} = nRT_H \ln\left(\frac{V_2}{V_1}\right) ### where ## n ## is the number of moles, ## R ## is the ideal gas constant, and ## V_1, V_2 ## are the initial and final volumes.

- Constant Volume (Isochoric) Heat Rejection (2-3): The working fluid passes through the regenerator, rejecting heat to it at constant volume as its temperature drops from ## T_H ## to ## T_C ##. No work is done in this phase. The heat rejected to the regenerator is: ### Q_{23} = nC_v(T_C - T_H) ### where ## C_v ## is the molar specific heat at constant volume.

- Isothermal Compression (3-4): The working fluid is compressed isothermally at the low temperature ## T_C ##, rejecting heat ## Q_C ## to the external heat sink. Work ## W_{34} ## is done on the fluid: ### Q_{34} = W_{34} = nRT_C \ln\left(\frac{V_4}{V_3}\right) ### where ## V_3, V_4 ## are the initial and final volumes of this stage. For a complete cycle ## V_1 = V_4 ## and ## V_2 = V_3 ##.

- Constant Volume (Isochoric) Heat Addition (4-1): The working fluid passes back through the regenerator, absorbing the stored heat at constant volume as its temperature rises from ## T_C ## to ## T_H ##. No work is done in this phase. The heat absorbed from the regenerator is: ### Q_{41} = nC_v(T_H - T_C) ###

The remarkable aspect of the Stirling cycle is that, ideally, the heat rejected to the regenerator in process 2-3 is perfectly reabsorbed from it in process 4-1. This internal heat transfer means that only external heat ## Q_H ## and ## Q_C ## need to be supplied and rejected, respectively. The net work done by the cycle is ## W_{net} = W_{12} + W_{34} ##. For an ideal Stirling engine, the thermal efficiency ## \eta_{Stirling} ## is identical to the Carnot efficiency:

### \eta_{Stirling} = 1 - \frac{T_C}{T_H} ###The Stirling engine can be configured in several ways:

- Alpha Configuration: Two separate power pistons in different cylinders, one hot and one cold, connected by a regenerator.

- Beta Configuration: A single cylinder with a power piston and a displacer piston, which moves the working fluid between the hot and cold ends.

- Gamma Configuration: Similar to Beta but with the power piston in a separate cylinder, less compact but simpler to build.

Despite its theoretical efficiency, practical Stirling engines face challenges, including maintaining large temperature differences across the hot and cold ends, achieving effective regeneration, and managing sealing issues with high-pressure working fluids like hydrogen or helium. These engines are notable for their quiet operation, ability to run on almost any heat source, and potential for use in niche applications such as solar power generation, waste heat recovery, and cryocoolers. Recent reports indicate renewed interest in Stirling technology for distributed power generation and space applications, as detailed by organizations like NASA.

Rankine Cycle Systems: The Dominance of Steam Power

The Rankine cycle is the fundamental thermodynamic cycle governing the operation of most conventional steam power plants, which are the primary source of electricity worldwide. Unlike the gaseous working fluid of the Stirling engine, the Rankine cycle utilizes a phase change (liquid-to-vapor and vapor-to-liquid) of its working fluid, typically water. The ideal Rankine cycle consists of four main processes, each occurring in a specific component:

- Isentropic Compression (1-2) in a Pump: Saturated liquid water from the condenser is pumped to a higher pressure. This process is ideally reversible and adiabatic (isentropic), meaning entropy remains constant. The work input to the pump is relatively small compared to the turbine output: ### W_{pump,in} = v_1(P_2 - P_1) ### where ## v_1 ## is the specific volume of the liquid at state 1, and ## P_1, P_2 ## are the pressures.

- Isobaric Heat Addition (2-3) in a Boiler: The high-pressure liquid enters the boiler, where it is heated at constant pressure by an external heat source (e.g., combustion of coal, natural gas, nuclear fission) until it becomes superheated vapor. This is where the primary heat input ## Q_{in} ## occurs. The heat added is: ### Q_{in} = h_3 - h_2 ### where ## h_2, h_3 ## are the specific enthalpies at states 2 and 3.

- Isentropic Expansion (3-4) in a Turbine: The high-pressure, high-temperature superheated steam expands through a turbine, generating mechanical work. This process is also ideally isentropic. The work output from the turbine is: ### W_{turbine,out} = h_3 - h_4 ### where ## h_3, h_4 ## are the specific enthalpies at states 3 and 4.

- Isobaric Heat Rejection (4-1) in a Condenser: The low-pressure steam from the turbine enters the condenser, where it is cooled at constant pressure, typically by cooling water, and condenses back into a saturated liquid. This is where heat ## Q_{out} ## is rejected to the surroundings: ### Q_{out} = h_4 - h_1 ###

The thermal efficiency of the Rankine cycle is given by:

### \eta_{Rankine} = \frac{W_{net}}{Q_{in}} = \frac{W_{turbine,out} - W_{pump,in}}{Q_{in}} = 1 - \frac{Q_{out}}{Q_{in}} ###The Rankine cycle is typically visualized on Temperature-Entropy (T-s) and Pressure-Volume (P-v) diagrams. On a T-s diagram, the dome represents the saturated liquid-vapor region. The efficiency of a Rankine cycle can be improved by several modifications:

- Superheating: Heating the steam to a temperature above its saturation temperature at a given pressure. This increases the average temperature at which heat is added and also reduces the moisture content at the turbine exhaust, preventing blade erosion.

- Reheating: After partial expansion in a high-pressure turbine, the steam is sent back to the boiler to be reheated before expanding further in a low-pressure turbine. This increases the average temperature of heat addition and reduces moisture.

- Regeneration (Feedwater Heating): A portion of the steam is extracted from the turbine at various stages and used to preheat the feedwater entering the boiler. This raises the temperature of the water before it enters the boiler, reducing the amount of external heat required and increasing efficiency. This process is crucial in large power plants.

While historically powering locomotives and ships, the Rankine cycle's primary modern application is in centralized power generation from fossil fuels, nuclear power, biomass, and concentrated solar power. Industry experts observe that advancements in metallurgy allowing for higher steam temperatures and pressures, along with sophisticated control systems, continue to push the boundaries of Rankine cycle efficiency, which can reach up to 45-50% in modern large-scale power plants.

Exploring Other External Combustion Engine Architectures

While the Stirling and Rankine cycles represent the most prominent ECE designs, several other architectures leverage external heat sources for power generation or propulsion. These alternative designs often target specific applications or aim to overcome limitations of the more common cycles.

The Ericsson Cycle

The Ericsson cycle is conceptually similar to the Stirling cycle, also employing isothermal expansion and compression with regenerative heat transfer. However, instead of constant volume heat addition and rejection, the Ericsson cycle features constant pressure (isobaric) heat addition and rejection. Like the ideal Stirling cycle, the ideal Ericsson cycle achieves Carnot efficiency. Its four reversible processes are:

- Isothermal Expansion (1-2): Heat is added at constant temperature ## T_H ##.

- Isobaric Heat Rejection (2-3): The working fluid is cooled at constant pressure through a regenerator.

- Isothermal Compression (3-4): Heat is rejected at constant temperature ## T_C ##.

- Isobaric Heat Addition (4-1): The working fluid is heated at constant pressure through a regenerator.

While theoretically efficient, practical implementation of the Ericsson cycle faces challenges similar to the Stirling engine, particularly concerning the perfect isothermal and isobaric processes and the effectiveness of the regenerator at high temperatures and pressures. Consequently, it has not seen widespread commercial adoption compared to the Stirling engine.

External Combustion Gas Turbines (ECGTs)

Conventional gas turbines operate on the Brayton cycle, where combustion occurs internally. However, it is possible to design an external combustion gas turbine. In an ECGT, air (or another gas) is heated indirectly by an external heat exchanger, often through combustion of a fuel. The heated gas then expands through a turbine to produce work, followed by a compressor stage. The primary advantage of an ECGT is its fuel flexibility, as it can utilize any heat source, similar to other ECEs. This makes them attractive for applications like coal-fired power plants (where direct combustion in a turbine is problematic due to ash and contaminants) or concentrated solar power where a heat transfer fluid heats the working gas. The cycle often involves a recuperator to recover heat from the turbine exhaust to preheat the compressed air, improving efficiency. The thermal efficiency of an ideal Brayton cycle with regeneration is:

### \eta_{Brayton,regen} = 1 - \frac{T_1}{T_3} \left(\frac{r_p^{(\gamma-1)/\gamma}}{\beta}\right) ###where ## T_1 ## is compressor inlet temperature, ## T_3 ## is turbine inlet temperature, ## r_p ## is pressure ratio, ## \gamma ## is specific heat ratio, and ## \beta ## is effectiveness of the recuperator.

Thermoelectric Generators (TEGs) and Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generators (RTGs)

While not "engines" in the mechanical sense of having moving parts driven by a working fluid, thermoelectric generators are a form of static external combustion system that convert heat directly into electricity using the Seebeck effect. RTGs, for instance, use the heat generated by the radioactive decay of a radioisotope (e.g., Plutonium-238) to create a temperature difference across a semiconductor material. This temperature difference induces an electric current. The efficiency of TEGs is typically lower than that of dynamic heat engines, often in the range of 5-10%, but their reliability, lack of moving parts, and long operational life make them invaluable for specific applications, particularly in space probes and remote power systems where maintenance is impossible. This technology is a cornerstone of deep space missions, as highlighted by endeavors at the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA).

Supercritical Carbon Dioxide (sCO2) Brayton Cycles

A promising area of research for ECEs is the use of supercritical carbon dioxide (sCO2) as a working fluid in a closed-loop Brayton cycle. CO2 enters its supercritical phase above 7.38 MPa and 31.0 °C. In this phase, it exhibits properties between a gas and a liquid, allowing for very high density and excellent heat transfer characteristics. The sCO2 cycle, often integrated with a regenerator/recuperator, can achieve high thermal efficiencies (potentially >50%) at relatively moderate temperatures compared to steam, with a much more compact turbomachinery due to the high density of sCO2. Its external heat input capability makes it suitable for nuclear power, concentrated solar power, and industrial waste heat recovery. Market analysis suggests that sCO2 cycles could be transformative for future compact and high-efficiency power generation systems.

Thermodynamic Limitations and Practical Efficiency Considerations

The efficiency of any heat engine, including ECEs, is fundamentally bounded by the Carnot limit, ## \eta_C = 1 - \frac{T_C}{T_H} ##. While ideal cycles like the Stirling and Ericsson cycles theoretically reach this limit, and the ideal Rankine cycle approaches it with increasing superheat and reheat, practical engines fall short due to a variety of irreversibilities. Understanding these limitations is crucial for engineering design and optimization.

- Heat Transfer Losses: Heat transfer from the combustion gases to the working fluid, and from the working fluid to the heat sink, involves finite temperature differences. Heat transfer across a finite temperature difference is inherently irreversible, leading to entropy generation and reducing overall efficiency. Furthermore, heat losses to the surroundings from hot components (e.g., boiler walls, piping) are unavoidable.

- Friction: Mechanical friction in bearings, pistons, and other moving parts converts useful mechanical energy into waste heat. Fluid friction (pressure drops) within pipes, valves, and heat exchangers also dissipates energy.

- Non-ideal Working Fluid Behavior: Real gases and vapors do not always perfectly follow ideal gas laws or the simplified thermodynamic properties assumed in ideal cycle analysis. Variations in specific heats, compressibility effects, and intermolecular forces can lead to deviations.

- Combustion Inefficiency: Although external combustion offers better control, imperfect combustion (e.g., incomplete oxidation of fuel) still means that not all the chemical energy in the fuel is converted into heat.

- Pump and Turbine/Expander Irreversibilities: The compression and expansion processes in real pumps, compressors, turbines, and expanders are not perfectly isentropic. Fluid viscosity, turbulence, and blade losses reduce their efficiencies below the ideal. The isentropic efficiency of a turbine (## \eta_T ##) and a pump (## \eta_P ##) are defined as: ### \eta_T = \frac{W_{actual}}{W_{isentropic}} \quad \text{and} \quad \eta_P = \frac{W_{isentropic}}{W_{actual}} ### where ## W_{actual} ## is the actual work and ## W_{isentropic} ## is the work for an ideal isentropic process.

- Regenerator Effectiveness: For engines like the Stirling and Ericsson cycles, the effectiveness of the regenerator is critical. An ideal regenerator transfers 100% of the heat between the hot and cold streams. A real regenerator will have finite heat transfer area, pressure drops, and thermal losses, reducing its effectiveness and thus the overall cycle efficiency. The regenerator effectiveness ## \epsilon ## is defined as: ### \epsilon = \frac{Q_{actual}}{Q_{max}} ### where ## Q_{actual} ## is the actual heat transferred and ## Q_{max} ## is the maximum possible heat transfer.

Engineers strive to minimize these irreversibilities through careful design, advanced materials, and optimized operating conditions. For instance, increasing the superheat and reheat in Rankine cycles or using higher-pressure working fluids in Stirling engines aims to raise the average temperature of heat addition, bringing the cycle closer to the Carnot limit. Advanced theoretical frameworks like exergy analysis are used to quantify the destruction of useful energy (exergy) at each stage of a process, pinpointing areas where efficiency improvements can have the greatest impact. Further technical guidelines are routinely published by professional bodies such as the American Society of Mechanical Engineers (ASME).

Engineering Challenges in System Design and Optimization

The development and optimization of external combustion engines present a unique set of engineering challenges that span material science, fluid mechanics, heat transfer, and control systems. Overcoming these challenges is crucial for enhancing performance, reliability, and cost-effectiveness.

- High-Temperature Material Selection: ECEs, particularly those aiming for high efficiency, operate at very high temperatures to maximize the ## T_H/T_C ## ratio. This demands materials that can withstand extreme temperatures, thermal cycling, creep, and corrosion. Superalloys, ceramics, and specialized composites are often necessary for components like boiler tubes, heat exchangers, and turbine blades. The structural integrity of these materials under prolonged high-temperature exposure is a critical design constraint.

- Heat Exchanger Design: Efficient heat transfer is paramount. Designing compact, high-effectiveness heat exchangers that can transfer large amounts of heat with minimal pressure drop and weight is a complex task. For Stirling engines, the design of the regenerator is particularly challenging, requiring materials with high specific heat capacity and low thermal conductivity in the flow direction, but high thermal conductivity perpendicular to it for rapid heat transfer. For Rankine cycles, boilers and condensers must handle phase changes efficiently across wide temperature and pressure ranges.

- Sealing Technology: For closed-cycle ECEs, especially Stirling engines using light gases like helium or hydrogen, maintaining a perfect seal to prevent working fluid leakage is a significant challenge. These gases have small molecular sizes and can permeate through many conventional sealing materials. Dynamic seals around moving piston rods must be robust and low-friction, contributing to mechanical losses if not optimized.

- Control Systems for Variable Loads: ECEs, especially those with large thermal masses like steam plants, can have slow response times to changes in load. Designing sophisticated control systems that can quickly and efficiently adjust heat input, working fluid flow rates, and engine speed to match power demand is crucial for practical applications. This includes managing start-up and shut-down sequences.

- Scaling and Miniaturization: Scaling ECE designs up for large power generation (e.g., utility-scale steam turbines) or down for micro-CHP (combined heat and power) units or portable applications (e.g., small Stirling engines) introduces distinct challenges. Heat transfer surface-to-volume ratios, mechanical losses, and manufacturing tolerances become disproportionately significant at different scales.

- Working Fluid Management: For Rankine cycles, managing water chemistry to prevent scaling and corrosion in boilers and condensers is vital for long-term operation. For Stirling engines, selecting the optimal working fluid (air, nitrogen, helium, hydrogen) involves trade-offs between thermal properties, cost, and sealing difficulty.

These engineering challenges necessitate a multidisciplinary approach, combining theoretical analysis with advanced computational modeling (e.g., Computational Fluid Dynamics - CFD, Finite Element Analysis - FEA) and extensive experimental validation. According to latest updates from research institutions, continuous innovation in materials science and manufacturing processes is critical to unlocking the full potential of advanced ECEs.

Environmental Implications and the Path to Sustainable Power

External combustion engines, by their inherent design, offer several compelling advantages concerning environmental impact and their role in the transition to sustainable energy systems. Their fuel flexibility is a primary asset in this regard.

- Fuel Flexibility and Reduced Emissions: Because the combustion is external, ECEs can utilize a vast array of heat sources. This includes renewable sources like solar thermal energy (concentrated solar power plants), geothermal energy, and biomass combustion. They can also efficiently convert waste heat from industrial processes into useful power. When using fossil fuels, the steady and controlled nature of external combustion allows for optimized combustion conditions, leading to more complete fuel oxidation and consequently lower emissions of harmful pollutants like carbon monoxide (CO), unburnt hydrocarbons (UHCs), and particulate matter (PM) compared to typical internal combustion engines. Furthermore, advanced flue gas treatment technologies (e.g., Selective Catalytic Reduction for NOx, scrubbers for SOx) are more easily integrated into large-scale external combustion facilities.

- Combined Heat and Power (CHP) Systems: ECEs are particularly well-suited for Combined Heat and Power (CHP), also known as cogeneration. In a CHP system, the heat rejected by the engine (typically in the condenser of a Rankine cycle or the cold sink of a Stirling engine) is captured and utilized for heating buildings, industrial processes, or other thermal loads, rather than simply being discharged to the environment. This significantly increases the overall system efficiency (thermal plus electrical), often exceeding 80% for the energy utilized, thereby reducing total fuel consumption and greenhouse gas emissions for a given energy demand.

- Integration with Renewable Energy Sources: ECEs, particularly Stirling engines and sCO2 Brayton cycles, are excellent candidates for integration with intermittent renewable energy sources. For example, a Stirling engine can run on heat from a concentrated solar collector, providing electricity during daylight hours. Similarly, sCO2 cycles are being explored for next-generation nuclear reactors and advanced geothermal plants, offering high efficiency and compactness. The ability to use diverse heat sources means ECEs can play a crucial role in diversifying our energy mix away from exclusive reliance on fossil fuels.

- Noise and Vibration: Stirling engines, in particular, are known for their quiet operation and low vibration due to their continuous combustion and sealed working fluid system. This makes them attractive for distributed power generation in urban or noise-sensitive environments, unlike the pulsating combustion and mechanical noise associated with many ICEs.

Despite these advantages, the environmental footprint of ECEs is not without considerations. Large-scale steam power plants, while benefiting from fuel flexibility, can still contribute significantly to CO2 emissions if fossil fuels are used without carbon capture technologies. The thermal pollution from rejected heat into cooling water bodies is another environmental concern. Nonetheless, the inherent characteristics of ECEs—especially their adaptability to diverse, cleaner heat sources and their high overall efficiency in CHP applications—position them as vital components in a future characterized by diversified and sustainable energy production. Discussions on energy and environmental policy are often provided by organizations such as Reuters or other global news outlets.

The Evolving Horizon of External Thermal Machines

The journey of external combustion engines, from their historical dominance in the age of steam to their current role in baseline power generation and niche applications, is a testament to their thermodynamic robustness. While often overshadowed by the rapid advancements in internal combustion engines for mobile applications, ECEs continue to evolve, driven by global demands for cleaner energy, higher efficiencies, and greater fuel flexibility.

Current research and development efforts are focused on several fronts. For Stirling engines, advancements in high-temperature materials, sealing technologies, and regenerator design aim to unlock their full potential for waste heat recovery, distributed solar power, and even specialized aerospace applications. The development of free-piston Stirling engines offers benefits in terms of mechanical simplicity and potential for long-life operation without lubrication, making them suitable for remote or unattended power generation.

In the realm of Rankine cycles, the push is towards "advanced Rankine cycles" utilizing supercritical working fluids like sCO2 or organic fluids (Organic Rankine Cycles, ORCs) for lower-temperature heat sources such as geothermal, biomass, and industrial waste heat. These cycles offer the promise of higher efficiencies at diverse temperature ranges and often with more compact turbomachinery. The development of advanced steam cycles, including ultra-supercritical and advanced ultra-supercritical steam plants, continues to push the boundaries of efficiency for large-scale power generation, utilizing steam temperatures and pressures far beyond those imagined a century ago.

Furthermore, the inherent ability of ECEs to integrate seamlessly with various renewable energy sources—be it concentrating solar thermal, geothermal, or biomass combustion—positions them as critical enablers for a decarbonized energy future. Their role in combined heat and power systems remains invaluable for maximizing resource utilization and reducing overall energy footprints in industrial and urban settings.

As the world seeks more efficient, flexible, and environmentally responsible methods of energy conversion, external combustion engines, far from being relics of the past, are undergoing a renaissance. Their foundational thermodynamic principles, coupled with relentless engineering innovation, ensure their continued relevance in the multifaceted tapestry of global power generation and thermal management. The careful balance of theoretical ideals and practical constraints will shape their trajectory, affirming their enduring significance in the evolving landscape of energy technology.

Also Read

RESOURCES

- Thermodynamics - Wikipedia

- Thermodynamics | Laws, Definition, & Equations | Britannica

- Why the hell is thermodynamics so confusing? : r/AskPhysics

- Thermodynamics

- Basics of Thermodynamics

- Thermodynamics - Lab Apparatus - Products | PASCO

- Thermodynamics (Dover Books on Physics): Fermi, Enrico ...

- Thermodynamics-based metabolic flux analysis

- Thermodynamics – Dover Publications

- ENGS 25 - Introduction to Thermodynamics |… | Dartmouth ...

- A two-dimensional volatility basis set: 1. organic-aerosol ... - ACP

- Statistical thermodynamics of liquid mixtures: A new expression for ...

- Process Systems, Reaction Engineering, and Molecular ...

- Home - European Thermodynamics Limited

- Thermodynamics of mixed‐gas adsorption - Myers - 1965 - AIChE ...

1 Comment