In the modern world, energy storage is not just a convenience; it is a foundational pillar of countless technologies that define daily life. From the smartphones in our pockets to electric vehicles on our roads and the rise of renewable power systems, one technology stands out as the dominant force: the lithium-ion battery. These compact powerhouses have transformed portable electronics and are central to the transition toward cleaner energy. Their widespread adoption, however, also makes one thing equally important: understanding how they work and how to use them safely.

On This Page

- The Core Science: How Lithium-Ion Batteries Work

- Battery Chemistries: Why Some Li-ion Batteries Feel “Different”

- Performance Metrics: Wh, Ah, W — and Why They Confuse People

- Advantages and Pervasive Applications

- Battery Lifespan: Why Batteries Age (Even When We “Do Nothing”)

- Battery Management Systems (BMS): The Hidden Safety Layer

- Imperative Safety Practices for Lithium-Ion Batteries

- Extending Battery Life With Smart Usage

- Simple Math and Numerical Intuition (Useful for Students)

- Programming Examples: Runtime and Charge-Time Estimates

- Code Example 1: Battery Runtime Estimator (Wh-based)

- Code Example 2: Power Bank mAh to Wh, Then Runtime

- Code Example 3: Variable Load (Duty Cycle) Runtime

- Code Example 4: Multi-Cell Packs (Series/Parallel) Wh and Runtime

- Code Example 5: CLI Tool (Runtime from Wh)

- Variation A: Plot Runtime vs Load (Quick Insight)

- Variation B: Unit-Test Style Checks (Sanity)

- Code Example 1: Rough Charge Time Estimator (Current-limited stage)

- Code Example 2: Charge Time from Charger Power Limit (W)

- Code Example 3: C-Rate Based Charging Estimate

- Code Example 4: Two-Stage CC + CV Approximation

- Code Example 5: CLI Tool (Charge Time from Ah and A)

- Variation A: Compare Two Chargers (Same Battery)

- Variation B: Thermal Throttle Model (Simple)

- Code Example 1: Storage SoC Reminder Helper

- Code Example 2: Add Temperature-Aware Storage Advice

- Code Example 3: Storage Checklist Generator (Printable Text)

- Code Example 4: Reminder Scheduler (Date Calculation)

- Code Example 5: Logging Storage Status to a File

- Variation A: Strict Policy Bands (Configurable)

- Variation B: Batch Evaluate a Fleet (Multiple Devices)

- The Horizon: Future of Lithium-Ion Technology

- Conclusion: Using Lithium-Ion Batteries Responsibly

We Also Published

This guide explains lithium-ion batteries in a practical, exam-friendly, and real-world-ready way. We will cover the core science, chemistry types, performance metrics, degradation, and most importantly, the safety practices that prevent overheating and thermal runaway. We will also include clean tables and a few programming examples to help compute battery runtime, charge time estimates, and safe storage reminders.

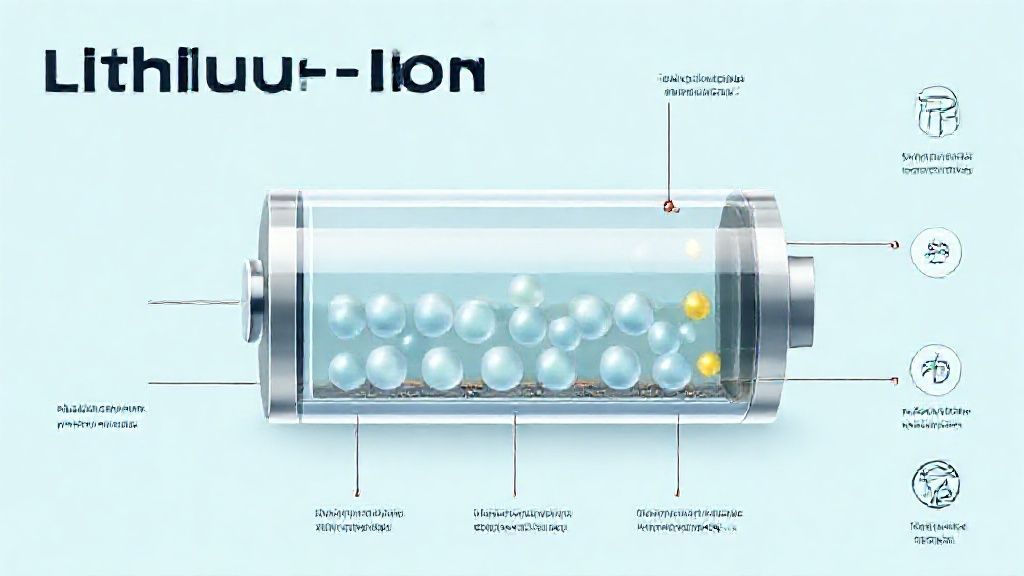

The Core Science: How Lithium-Ion Batteries Work

At its heart, a lithium-ion (Li-ion) battery is an electrochemical system that stores and releases energy through the reversible movement of lithium ions between two electrodes. A typical Li-ion cell contains:

What Happens During Discharge and Charge?

During discharge (battery powering a device), lithium ions move from the anode to the cathode through the electrolyte, while electrons travel through the external circuit to do useful work.

During charging, an external charger forces the reverse process: lithium ions are driven from cathode back to anode, and electrons are pushed back through the circuit into the anode.

| Term | Meaning | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Cell | One electrochemical unit (e.g., 18650, pouch cell) | Cells are combined to make battery packs |

| Pack | Many cells plus wiring, BMS, casing | Packs add safety electronics and thermal design |

| SoC | State of Charge (0–100%) | Operating in a mid-range often improves longevity |

| DoD | Depth of Discharge | Deeper cycles generally age batteries faster |

| C-rate | Charge/discharge current relative to capacity | High C-rate increases heating and stress |

| Thermal runaway | Self-heating chain reaction inside the battery | Main safety risk leading to fire if uncontrolled |

Battery Chemistries: Why Some Li-ion Batteries Feel “Different”

Not all lithium-ion batteries are the same. The cathode chemistry strongly influences energy density, power capability, lifespan, and safety behavior. Common chemistries include:

| Chemistry | Strength | Trade-off | Common Use |

|---|---|---|---|

| LCO | High energy density | Shorter cycle life, more sensitive to heat | Portable electronics |

| NMC / NCA | Good balance (energy + power) | Thermal management important at high loads | EVs, tools, e-bikes |

| LFP | Thermally stable, long cycle life | Lower energy density (heavier for same range) | EV packs, home storage |

Performance Metrics: Wh, Ah, W — and Why They Confuse People

Battery marketing often mixes capacity (Ah or mAh) with energy (Wh). For realistic comparisons, Wh (watt-hour) is more meaningful than mAh because it includes voltage.

For example, a 3.7V battery rated 5Ah has:

If a device consumes ~5W, the ideal runtime (ignoring losses) is:

Real runtime is lower because of conversion losses, temperature effects, and high current draw. This is where a battery management system (BMS) and good thermal design become essential.

Advantages and Pervasive Applications

Lithium-ion dominates because it offers:

These advantages place Li-ion at the center of:

Battery Lifespan: Why Batteries Age (Even When We “Do Nothing”)

Li-ion batteries degrade through two broad pathways:

Major Degradation Factors

A Practical Battery Health Window

Many users extend battery life by operating mostly in a mid-range SoC window when possible (commonly cited as roughly 20%–80%). This is not a strict rule for every device, but as a general habit it reduces stress, particularly for devices that sit plugged in for hours. Modern devices often include battery health features that “pause” at 80% and finish charging near the time of use.

For deeper research and public-facing guidance, we can refer to initiatives and educational material from the U.S. Department of Energy energy storage programs, which discuss storage systems, R&D focus areas, and safety considerations.

Battery Management Systems (BMS): The Hidden Safety Layer

A BMS is the electronics and firmware that acts like a “battery guardian.” In many products, the BMS provides:

This is why using unknown or counterfeit battery packs is risky: the safety circuitry may be absent, poorly designed, or incorrectly calibrated.

Imperative Safety Practices for Lithium-Ion Batteries

Li-ion batteries contain flammable electrolyte and store significant energy in compact volume. The main risks involve overcharging, physical damage, internal short circuits, and excess heat, all of which can trigger thermal runaway.

What Is Thermal Runaway?

Thermal runaway is a chain reaction where rising temperature inside the battery accelerates chemical reactions that produce even more heat. Without control, it can lead to venting, fire, or explosion. The best strategy is prevention: correct charging, avoiding damage, and stopping use if warning signs appear.

Safety Checklist: Practical Dos and Don’ts

| Situation | Do | Do Not |

|---|---|---|

| Charging | Use OEM or certified chargers; charge on hard, non-flammable surfaces | Use cheap counterfeit chargers or charge under pillows/beds |

| Heat exposure | Keep devices away from direct sunlight in cars and hot windowsills | Leave batteries in parked cars in summer heat |

| Physical integrity | Stop using if swollen, punctured, leaking, or smelling unusual | Puncture, crush, bend, or attempt DIY “repair” of cells |

| Storage | Store cool and dry, ideally around mid-charge for long storage | Store fully charged or fully empty for months |

| Disposal | Recycle at authorized centers | Throw in household trash or burn |

Warning Signs That Require Immediate Action

If these signs appear, discontinue use immediately, move the device to a safe non-flammable area (if it can be done safely), and follow manufacturer instructions for service/replacement. The goal is to avoid escalation, not to “test” the battery further.

Battery safety certification and testing standards are a major part of safe product engineering. Organizations like UL Solutions provide certification services and safety benchmarks used across many industries.

Extending Battery Life With Smart Usage

Safety and longevity often improve together. These habits reduce stress:

Myths vs Facts

| Claim | Reality | Practical Takeaway |

|---|---|---|

| “We must fully discharge to calibrate.” | Frequent full discharge is not ideal for Li-ion. | Occasional calibration may help some devices, but do not do it routinely. |

| “Fast charging always ruins batteries.” | Not always; modern systems manage heat and current in stages. | Heat is the key. Keep charging cool and use fast charge when needed. |

| “Leaving it plugged in always overcharges.” | Most devices stop charging at full and run from adapter power. | Still, long high-SoC exposure can age batteries, so health limits help. |

| “All lithium batteries are the same.” | Chemistry and pack engineering differ greatly. | LFP behaves differently than NMC; always follow device guidance. |

Simple Math and Numerical Intuition (Useful for Students)

Two quick relationships help us reason about batteries:

Programming Examples: Runtime and Charge-Time Estimates

The following examples are educational and help compute runtime/charge estimates. They do not instruct any unsafe battery modification. All code is HTML-escaped and ready for your code-wrapper pipeline.

Code Example 1: Battery Runtime Estimator (Wh-based)

def battery_energy_wh(nominal_voltage_v: float, capacity_ah: float) -> float:

"""

Energy in watt-hours (Wh) = Voltage (V) * Capacity (Ah)

This is a better comparison metric than mAh alone.

"""

if nominal_voltage_v <= 0 or capacity_ah <= 0:

raise ValueError("Voltage and capacity must be positive.")

return nominal_voltage_v * capacity_ah

def estimated_runtime_hours(energy_wh: float, load_watts: float, efficiency: float = 0.85) -> float:

"""

Estimated runtime (hours) = (Energy Wh * efficiency) / Load W

Efficiency accounts for conversion losses and real-world factors.

"""

if energy_wh <= 0 or load_watts <= 0:

raise ValueError("Energy and load must be positive.")

if not (0 < efficiency <= 1):

raise ValueError("Efficiency must be in (0, 1].")

return (energy_wh * efficiency) / load_watts

# Example: 3.7V, 5Ah battery powering a 5W device

V = 3.7

Ah = 5.0

load = 5.0

wh = battery_energy_wh(V, Ah)

hours = estimated_runtime_hours(wh, load, efficiency=0.85)

print("Battery energy (Wh):", wh)

print("Estimated runtime (hours):", hours)

Explanation: This uses ##\text{Wh}=V\times Ah## and divides by load power. Efficiency is included because real devices lose energy in conversion and internal resistance.

Code Example 2: Power Bank mAh to Wh, Then Runtime

def powerbank_wh_from_mah(mah: float, cell_voltage_v: float = 3.7) -> float:

# Convert mAh at nominal cell voltage to Wh

# Wh = (mAh / 1000) * V

if mah <= 0 or cell_voltage_v <= 0:

raise ValueError("mAh and voltage must be positive.")

return (mah / 1000.0) * cell_voltage_v

def runtime_hours_from_wh(energy_wh: float, device_w: float, efficiency: float = 0.8) -> float:

# Estimate runtime with a conservative efficiency (USB boost + cable losses)

if energy_wh <= 0 or device_w <= 0:

raise ValueError("Energy and device power must be positive.")

if not (0 < efficiency <= 1):

raise ValueError("Efficiency must be in (0, 1].")

return (energy_wh * efficiency) / device_w

# Example: 10,000 mAh power bank (cells @ 3.7V) powering a 7W load

mah = 10_000

device_w = 7.0

energy_wh = powerbank_wh_from_mah(mah, cell_voltage_v=3.7)

hours = runtime_hours_from_wh(energy_wh, device_w, efficiency=0.8)

print("Estimated energy (Wh):", energy_wh)

print("Estimated runtime (hours):", hours)

Explanation: Many power banks advertise mAh at ~3.7V internal cells, not at 5V USB output. Converting to Wh first gives a fair comparison. Replace device_w with the real power draw of the device.

- Replace

mahanddevice_wwith actual values. - Adjust

efficiencyfor real-world losses (boost conversion, cable, heat).

Code Example 3: Variable Load (Duty Cycle) Runtime

def average_power_w(active_w: float, idle_w: float, active_fraction: float) -> float:

# Weighted average power for devices that alternate between active and idle

if active_w < 0 or idle_w < 0:

raise ValueError("Power values must be non-negative.")

if not (0 <= active_fraction <= 1):

raise ValueError("active_fraction must be in [0, 1].")

return (active_w * active_fraction) + (idle_w * (1 - active_fraction))

def runtime_hours(energy_wh: float, avg_w: float, efficiency: float = 0.85) -> float:

# Runtime based on average power draw

if energy_wh <= 0 or avg_w <= 0:

raise ValueError("Energy and average power must be positive.")

if not (0 < efficiency <= 1):

raise ValueError("Efficiency must be in (0, 1].")

return (energy_wh * efficiency) / avg_w

# Example: Sensor node: 2W active 10% of time, 0.2W idle 90% of time

energy_wh = 18.5 # Example battery energy (Wh)

avg_w = average_power_w(active_w=2.0, idle_w=0.2, active_fraction=0.10)

hours = runtime_hours(energy_wh, avg_w, efficiency=0.9)

print("Average power (W):", avg_w)

print("Estimated runtime (hours):", hours)

Explanation: Some devices draw high power briefly and low power most of the time. Estimating with average power often matches reality better than using peak power continuously.

Code Example 4: Multi-Cell Packs (Series/Parallel) Wh and Runtime

def pack_wh(cell_v: float, cell_ah: float, series: int, parallel: int) -> float:

# Series increases voltage; parallel increases capacity (Ah)

if cell_v <= 0 or cell_ah <= 0:

raise ValueError("Cell voltage and Ah must be positive.")

if series <= 0 or parallel <= 0:

raise ValueError("Series and parallel counts must be positive integers.")

pack_v = cell_v * series

pack_ah = cell_ah * parallel

return pack_v * pack_ah # Wh

def runtime_from_pack(series: int, parallel: int, cell_v: float, cell_ah: float, load_w: float, efficiency: float = 0.85) -> float:

# Combine pack energy with load to estimate runtime

energy = pack_wh(cell_v, cell_ah, series, parallel)

if load_w <= 0:

raise ValueError("Load must be positive.")

return (energy * efficiency) / load_w

# Example: 3S2P of 3.7V 2.5Ah cells powering a 20W load

hours = runtime_from_pack(series=3, parallel=2, cell_v=3.7, cell_ah=2.5, load_w=20.0, efficiency=0.9)

print("Estimated runtime (hours):", hours)

Explanation: For packs, compute effective voltage and capacity first. Series affects voltage; parallel affects Ah. Wh remains the consistent comparison metric across designs.

Code Example 5: CLI Tool (Runtime from Wh)

import argparse

def runtime_hours_from_wh(energy_wh: float, load_w: float, efficiency: float) -> float:

# Core calculation reused by the command-line interface

if energy_wh <= 0 or load_w <= 0:

raise ValueError("Energy and load must be positive.")

if not (0 < efficiency <= 1):

raise ValueError("Efficiency must be in (0, 1].")

return (energy_wh * efficiency) / load_w

def main() -> None:

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Estimate battery runtime from Wh and load power.")

parser.add_argument("--wh", type=float, required=True, help="Battery energy in Wh")

parser.add_argument("--load", type=float, required=True, help="Load power in W")

parser.add_argument("--eff", type=float, default=0.85, help="Efficiency in (0,1], default 0.85")

args = parser.parse_args()

hours = runtime_hours_from_wh(args.wh, args.load, args.eff)

print("Estimated runtime (hours):", hours)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Explanation: This wraps the same formula in a small CLI. Replace --wh and --load with real values. Use a conservative --eff to account for conversion losses.

- Example usage:

python tool.py --wh 18.5 --load 5 --eff 0.85 - Replace

tool.pywith your filename.

Variation A: Plot Runtime vs Load (Quick Insight)

def runtime_hours(energy_wh: float, load_w: float, eff: float = 0.85) -> float:

# Simple helper reused in a loop to generate a load sweep

return (energy_wh * eff) / load_w

energy_wh = 18.5

eff = 0.85

# Load sweep from 1W to 15W (integer steps)

for load_w in range(1, 16):

print(load_w, "W ->", runtime_hours(energy_wh, float(load_w), eff), "hours")

Explanation: Sweeping load power shows how runtime drops as power demand increases. Replace energy_wh with your real battery energy estimate.

Variation B: Unit-Test Style Checks (Sanity)

def battery_wh(v: float, ah: float) -> float:

# Compute Wh and validate

if v <= 0 or ah <= 0:

raise ValueError("Inputs must be positive.")

return v * ah

def runtime(wh: float, w: float, eff: float) -> float:

# Compute runtime in hours

if wh <= 0 or w <= 0:

raise ValueError("Inputs must be positive.")

if not (0 < eff <= 1):

raise ValueError("Efficiency must be in (0, 1].")

return (wh * eff) / w

# Basic sanity checks (not a full test framework)

assert round(battery_wh(3.7, 5.0), 2) == 18.50

assert round(runtime(18.5, 5.0, 1.0), 2) == 3.70

print("Sanity checks passed.")

Explanation: Small assertions catch obvious mistakes (wrong units, negative inputs). Replace the expected values if you change parameters.

Code Example 1: Rough Charge Time Estimator (Current-limited stage)

def rough_charge_time_hours(capacity_ah: float, charge_current_a: float, overhead_factor: float = 1.2) -> float:

"""

Rough estimate for charge time in hours:

time ≈ (Ah / A) * overhead_factor

overhead_factor approximates tapering/inefficiency during the later charging stage.

Real devices may take longer depending on thermal limits and charge protocols.

"""

if capacity_ah <= 0 or charge_current_a <= 0:

raise ValueError("Capacity and current must be positive.")

if overhead_factor < 1:

raise ValueError("overhead_factor should be >= 1.")

return (capacity_ah / charge_current_a) * overhead_factor

# Example: 5Ah battery charged at 2A

Ah = 5.0

I = 2.0

t_hours = rough_charge_time_hours(Ah, I, overhead_factor=1.25)

print("Rough charge time (hours):", t_hours)

Explanation: Li-ion charging typically includes a constant-current stage followed by a voltage-hold taper, so simple Ah/A underestimates time. The overhead factor approximates that taper.

Code Example 2: Charge Time from Charger Power Limit (W)

def charge_time_from_power(energy_wh: float, charger_w: float, system_eff: float = 0.85, overhead_factor: float = 1.15) -> float:

# Estimate charge time using power (useful for USB-PD adapters)

if energy_wh <= 0 or charger_w <= 0:

raise ValueError("Energy and charger power must be positive.")

if not (0 < system_eff <= 1):

raise ValueError("system_eff must be in (0, 1].")

if overhead_factor < 1:

raise ValueError("overhead_factor should be >= 1.")

effective_w = charger_w * system_eff

base_hours = energy_wh / effective_w

return base_hours * overhead_factor

# Example: 18.5 Wh battery, 15 W charger (USB-PD), typical losses and taper

t = charge_time_from_power(energy_wh=18.5, charger_w=15.0, system_eff=0.85, overhead_factor=1.2)

print("Estimated charge time (hours):", t)

Explanation: Some devices are adapter-limited (watts) rather than current-limited. This estimates time as Wh / W, then inflates it for taper/thermal throttling via overhead_factor.

Code Example 3: C-Rate Based Charging Estimate

def charge_current_from_c_rate(capacity_ah: float, c_rate: float) -> float:

# I(A) = C-rate * capacity(Ah)

if capacity_ah <= 0 or c_rate <= 0:

raise ValueError("capacity_ah and c_rate must be positive.")

return capacity_ah * c_rate

def rough_charge_time_hours(capacity_ah: float, current_a: float, overhead: float = 1.2) -> float:

# Same pattern: (Ah / A) times a taper factor

if capacity_ah <= 0 or current_a <= 0:

raise ValueError("capacity_ah and current_a must be positive.")

if overhead < 1:

raise ValueError("overhead must be >= 1.")

return (capacity_ah / current_a) * overhead

# Example: 5Ah battery charged at 0.5C

ah = 5.0

c_rate = 0.5

current = charge_current_from_c_rate(ah, c_rate)

t = rough_charge_time_hours(ah, current, overhead=1.25)

print("Charge current (A):", current)

print("Estimated charge time (hours):", t)

Explanation: C-rate expresses current relative to capacity. For example, 0.5C means charging at half the capacity in amps. Replace c_rate with your device/battery rating if known.

Code Example 4: Two-Stage CC + CV Approximation

def cc_cv_charge_time_hours(capacity_ah: float, cc_current_a: float, cc_fraction: float = 0.7, cv_multiplier: float = 0.6) -> float:

"""

Simple two-stage approximation:

- CC stage charges ~cc_fraction of capacity at cc_current_a

- CV stage charges remaining capacity at an "effective" lower current (cv_multiplier * cc_current_a)

"""

if capacity_ah <= 0 or cc_current_a <= 0:

raise ValueError("capacity_ah and cc_current_a must be positive.")

if not (0 < cc_fraction < 1):

raise ValueError("cc_fraction must be in (0, 1).")

if not (0 < cv_multiplier < 1):

raise ValueError("cv_multiplier must be in (0, 1).")

cc_ah = capacity_ah * cc_fraction

cv_ah = capacity_ah - cc_ah

t_cc = cc_ah / cc_current_a

t_cv = cv_ah / (cc_current_a * cv_multiplier)

return t_cc + t_cv

# Example: 5Ah pack, 2A CC stage, 70% CC fraction, CV effective current ~60% of CC

t = cc_cv_charge_time_hours(capacity_ah=5.0, cc_current_a=2.0, cc_fraction=0.7, cv_multiplier=0.6)

print("Approx CC+CV charge time (hours):", t)

Explanation: This splits charging into a faster CC portion and a slower CV taper. Replace cc_fraction and cv_multiplier to match typical behavior for your device (taper can be more aggressive under heat).

Code Example 5: CLI Tool (Charge Time from Ah and A)

import argparse

def rough_charge_time_hours(capacity_ah: float, current_a: float, overhead: float) -> float:

# Core formula with taper/inefficiency overhead

if capacity_ah <= 0 or current_a <= 0:

raise ValueError("capacity_ah and current_a must be positive.")

if overhead < 1:

raise ValueError("overhead must be >= 1.")

return (capacity_ah / current_a) * overhead

def main() -> None:

parser = argparse.ArgumentParser(description="Rough Li-ion charge time estimate (Ah/A + overhead).")

parser.add_argument("--ah", type=float, required=True, help="Battery capacity in Ah")

parser.add_argument("--a", type=float, required=True, help="Charge current in A (CC stage)")

parser.add_argument("--overhead", type=float, default=1.2, help="Taper/inefficiency factor (default 1.2)")

args = parser.parse_args()

t = rough_charge_time_hours(args.ah, args.a, args.overhead)

print("Rough charge time (hours):", t)

if __name__ == "__main__":

main()

Explanation: This is a practical estimator for current-limited charging. Replace --ah and --a with real values. Increase --overhead if the device tapers early or throttles for heat.

Variation A: Compare Two Chargers (Same Battery)

def rough_charge_time_hours(ah: float, a: float, overhead: float = 1.25) -> float:

# Same estimate, reused to compare scenarios

return (ah / a) * overhead

battery_ah = 5.0

t_1a = rough_charge_time_hours(battery_ah, a=1.0, overhead=1.25)

t_2a = rough_charge_time_hours(battery_ah, a=2.0, overhead=1.25)

print("1A charger (hours):", t_1a)

print("2A charger (hours):", t_2a)

Explanation: Comparing currents shows why higher current reduces time, but real devices may cap current or reduce it under heat—so the difference is not always linear.

Variation B: Thermal Throttle Model (Simple)

def throttled_current(base_current_a: float, temp_c: float, throttle_start_c: float = 35.0, min_factor: float = 0.5) -> float:

# If temperature exceeds throttle_start_c, reduce current linearly down to min_factor

if base_current_a <= 0:

raise ValueError("base_current_a must be positive.")

if min_factor <= 0 or min_factor > 1:

raise ValueError("min_factor must be in (0, 1].")

if temp_c <= throttle_start_c:

return base_current_a

# Every 10C above throttle_start reduces current further (simple educational model)

over = temp_c - throttle_start_c

factor = max(min_factor, 1.0 - (over / 20.0)) # clamp to min_factor

return base_current_a * factor

def rough_charge_time_hours(ah: float, current_a: float, overhead: float = 1.25) -> float:

# Use adjusted current in the standard estimator

return (ah / current_a) * overhead

battery_ah = 5.0

base_current = 2.0

for temp in [25, 35, 40, 45]:

adj = throttled_current(base_current, temp)

t = rough_charge_time_hours(battery_ah, adj, overhead=1.25)

print(temp, "C - current:", adj, "A - time:", t, "h")

Explanation: Heat often forces current reduction. This toy model demonstrates the direction of the effect (higher temperature → longer charge time). Replace the throttle logic with device-specific behavior if known.

Code Example 1: Storage SoC Reminder Helper

def storage_guidance(soc_percent: float) -> str:

"""

Practical guidance for long-term storage:

Many users store around mid-charge to reduce stress.

This does not override manufacturer instructions.

"""

if soc_percent < 0 or soc_percent > 100:

raise ValueError("SoC must be between 0 and 100.")

if soc_percent < 15:

return "SoC is very low. For long storage, consider charging a bit to a mid-range if device guidance allows."

if 15 <= soc_percent <= 70:

return "SoC is in a reasonable mid-range for storage in many cases (keep cool and dry)."

if 70 < soc_percent <= 100:

return "SoC is high. For long storage, mid-range is often gentler; avoid heat and follow device instructions."

# Example checks

for soc in [5, 45, 90]:

print(soc, "-", storage_guidance(soc))

Explanation: This is a simple educational helper. Real devices vary, so manufacturer guidance remains the priority.

Code Example 2: Add Temperature-Aware Storage Advice

def storage_guidance_with_temp(soc_percent: float, temp_c: float) -> str:

# Educational helper: SoC guidance + temperature risk note

if soc_percent < 0 or soc_percent > 100:

raise ValueError("SoC must be between 0 and 100.")

msg_parts = []

# Base SoC guidance

if soc_percent < 15:

msg_parts.append("SoC is very low; avoid storing near empty if guidance allows a mid-range top-up.")

elif soc_percent <= 70:

msg_parts.append("SoC is in a mid-range that is often gentler for storage.")

else:

msg_parts.append("SoC is high; long storage at high SoC can increase aging risk.")

# Temperature note

if temp_c >= 35:

msg_parts.append("Temperature is high; heat accelerates aging. Move storage to a cooler location.")

elif temp_c <= 0:

msg_parts.append("Temperature is very low; avoid charging if the pack is too cold.")

else:

msg_parts.append("Temperature is moderate; keep dry and avoid large swings.")

return " ".join(msg_parts)

# Example: Check combinations

cases = [(45, 25), (90, 38), (10, 15)]

for soc, temp in cases:

print("SoC:", soc, "Temp:", temp, "-", storage_guidance_with_temp(soc, temp))

Explanation: This adds a temperature note because heat can speed up aging. Replace temperature thresholds with device-specific guidance if available.

Code Example 3: Storage Checklist Generator (Printable Text)

def storage_checklist(soc_percent: float) -> str:

# Returns a short checklist string that can be printed or logged

if soc_percent < 0 or soc_percent > 100:

raise ValueError("SoC must be between 0 and 100.")

lines = []

lines.append("Storage Checklist:")

lines.append("- Keep in a cool, dry place.")

lines.append("- Avoid direct sunlight and heat sources.")

lines.append("- Check SoC every few months.")

if soc_percent < 15:

lines.append("- SoC is low: consider charging to a mid-range if guidance allows.")

elif soc_percent <= 70:

lines.append("- SoC is mid-range: generally reasonable for storage.")

else:

lines.append("- SoC is high: consider lowering to a mid-range for long storage if appropriate.")

return "\n".join(lines)

print(storage_checklist(45))

Explanation: This produces a simple checklist. Replace checklist items with organization/device policies where required.

Code Example 4: Reminder Scheduler (Date Calculation)

from datetime import date, timedelta

def next_check_date(interval_days: int = 60) -> date:

# Returns a date for the next storage check (e.g., every 60 days)

if interval_days <= 0:

raise ValueError("interval_days must be positive.")

return date.today() + timedelta(days=interval_days)

def reminder_message(soc_percent: float, interval_days: int = 60) -> str:

# Combine SoC guidance with a future check date

d = next_check_date(interval_days)

return f"SoC: {soc_percent}%. Next check on: {d.isoformat()}"

print(reminder_message(50, interval_days=90))

Explanation: This computes the next check date for periodic storage reviews. Replace interval_days with your preferred schedule (e.g., 60–120 days).

Code Example 5: Logging Storage Status to a File

from datetime import datetime

def log_storage_status(filepath: str, soc_percent: float, note: str) -> None:

# Append a single line log entry for storage status checks

if soc_percent < 0 or soc_percent > 100:

raise ValueError("SoC must be between 0 and 100.")

if not filepath:

raise ValueError("filepath must be a non-empty string.")

ts = datetime.now().isoformat(timespec="seconds")

line = f"{ts}\tSoC={soc_percent}%\t{note}\n"

with open(filepath, "a", encoding="utf-8") as f:

f.write(line)

# Example: log a status check

log_storage_status("battery_storage_log.txt", soc_percent=45, note="Stored in cool cabinet, away from sunlight.")

print("Logged storage status.")

Explanation: This appends a timestamped record for storage checks. Replace battery_storage_log.txt with your real path, and update note with relevant conditions (location, temperature, etc.).

Variation A: Strict Policy Bands (Configurable)

def storage_guidance_policy(soc_percent: float, low: float = 20.0, high: float = 60.0) -> str:

# Make thresholds configurable for different policies/devices

if soc_percent < 0 or soc_percent > 100:

raise ValueError("SoC must be between 0 and 100.")

if not (0 <= low <= high <= 100):

raise ValueError("Invalid band: ensure 0 <= low <= high <= 100.")

if soc_percent < low:

return f"Below policy band ({low}%–{high}%). Consider topping up if permitted."

if soc_percent > high:

return f"Above policy band ({low}%–{high}%). Consider reducing SoC for long storage if appropriate."

return f"Within policy band ({low}%–{high}%). Store cool and dry."

for soc in [10, 35, 80]:

print(soc, "-", storage_guidance_policy(soc, low=25, high=55))

Explanation: This makes SoC thresholds configurable. Replace low and high with your chosen policy band or device guidance.

Variation B: Batch Evaluate a Fleet (Multiple Devices)

def storage_guidance(soc: float) -> str:

# Minimal guidance reused in a batch loop

if soc < 0 or soc > 100:

raise ValueError("SoC must be between 0 and 100.")

if soc < 15:

return "Low SoC: consider mid-range top-up if allowed."

if soc <= 70:

return "Mid-range: generally reasonable for storage."

return "High SoC: consider mid-range for long storage; avoid heat."

devices = [

{"name": "Laptop A", "soc": 92},

{"name": "Drone Pack", "soc": 55},

{"name": "Spare Phone", "soc": 12},

]

for d in devices:

print(d["name"], "-", d["soc"], "% -", storage_guidance(d["soc"]))

Explanation: This applies the same guidance across multiple devices. Replace the devices list with real inventory values.

The Horizon: Future of Lithium-Ion Technology

Lithium-ion technology is still evolving rapidly. Key directions include:

Conclusion: Using Lithium-Ion Batteries Responsibly

Lithium-ion batteries power modern life because they offer strong energy density, efficiency, and versatility across devices, vehicles, and energy storage. The same compact energy that makes them so useful also makes safe usage non-negotiable. When we follow best practices—approved chargers, damage avoidance, heat control, and correct recycling—we reduce risk and extend battery life at the same time.

As battery technology advances toward safer designs and higher performance, informed everyday habits remain the first line of defense. With a clear understanding of how Li-ion cells work, what ages them, and what warning signs matter, we can use this transformative technology with confidence and care.

Also Read

From our network :

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/trump-political-strategy-how-geopolitical-stunts-serve-as-media-diversions

- https://www.themagpost.com/post/analyzing-trump-deportation-numbers-insights-into-the-2026-immigration-crackdown

- Mastering DB2 12.1 Instance Design: A Technical Deep Dive into Modern Database Architecture

- Mastering DB2 LUW v12 Tables: A Comprehensive Technical Guide

- 10 Physics Numerical Problems with Solutions for IIT JEE

- AI-Powered 'Precision Diagnostic' Replaces Standard GRE Score Reports

- Vite 6/7 'Cold Start' Regression in Massive Module Graphs

- 98% of Global MBA Programs Now Prefer GRE Over GMAT Focus Edition

- EV 2.0: The Solid-State Battery Breakthrough and Global Factory Expansion

RESOURCES

- Transporting Lithium Batteries | PHMSA

- Top Do's and Don'ts for Lithium Battery Safety

- Ebike Battery Storage Safety and Thermal Runaway Signs | All …

- Safest way to keep lithium batteries in the house? : r/batteries

- Home E Bike and Lithium Ion Battery Fire Safety | All Nation …

- Lithium-Ion Battery Safety: Expert Insights & Guidelines

- Preventing Fire and/or Explosion Injury from Small and Wearable …

- Lithium-ion Safety

- Fire Prevention Week – Day 4: Lithium-Ion Batteries Are Everywhere …

- Lithium-Ion Battery Safety

- Lithium-ion batteries can catch fire if damaged or improperly …

- Fire Prevention Week | News | American Red Cross

- SAFETY ALERT: Lithium-Ion Battery Fire Hazard This morning …

- Battery Safety During the Holidays An ever-increasing number of …

- Lithium-ion batteries, commonly used in cell phones, laptops …

3 Comments